The Middle East Reimagined

GB sits down in Amman with one of West Asia’s leading voices for regional reengineering

GB sits down in Amman with one of West Asia’s leading voices for regional reengineering

GB: What is the mood in Jordan today?

BT: The mood has moved from sombre, due to the uncertainty about the future of the Jordanian pilot – now the late first lieutenant Moaz Al Kasasbeh, as well as about the fate of the two Japanese journalists (in particular that of Kenji Goto, whose life seemed to be tied in some way to the deal that was being brokered for the pilot) – to the current frantic mode, which was triggered when people witnessed the unexpected immolation of the pilot. This was a gruesome sight, and quite unifying for people in their collective disgust and disdain. It brought the propaganda war to a head. Some people say that the organization that perpetrated this atrocity miscalculated because, whereas in northern Iraq and Syria it was able to move very quickly to secure territory through similar acts of brutality, this particular attempt to intimidate the general public led to a powerful reaction across the board: revulsion at what had happened, total repudiation of the organization and, like the Charlie Hebdo story, people marching in the street, essentially saying that we are all Moaz Al Kasasbeh. So the mood in Jordan at the moment is one of commitment to the long haul – to the fight against terrorism, and to attempting to stabilize the country.

GB: How do you see the conflicts in Syria and Iraq unfolding over the next six months? And what is the future of ISIS?

BT: The conflict between the Syrian government and resistance movements in Syria, in the context of the Arab Spring, has been unfolding since early 2011. As far as Iraq is concerned, its conflicts go back to the several wars in which that country has been involved since the Iraq-Iran War. Now, can we see emerging out of all this mayhem an attempt to stabilize the region? There are more militias today in the Middle East than there are governments. Indeed, ISIS is but one of a number of militias with different names that cross our screens from time to time – all with consequences for the internal security challenge for the region. So we evidently cannot reduce the conflict to a simple Sunni versus Shia dispute.

Remember that there are already 1.4 million Syrian refugees in Jordan. This represents about eight percent of the Jordanian population. And we in Jordan continue to be mindful of the sleeper factor – that one act of horror, such as the killing of some 60 people in Jordanian hotels in 2005, which remains very vivid in the minds of Jordanians.

GB: Does the Middle East need a regional security framework of some sort?

BT: If the EU was able to develop an Erasmus programme, this means that Russia, Ukraine and Belarus require a Chekhov, Tchaikovsky or Dostoyevsky programme. Perhaps, then, the Middle East, or West Asia – as it were – requires an Ibn Khaldun programme in order to change attitudes about each other, and to develop an international media Peace Corps that combines scholarship with media outlets, and gives content to some of the basic issues that we are all currently addressing in the Millennium Development Goals.

At present, I do not see any automatic coalescing of the oil and gas producing countries in the region with their neighbouring hinterland peoples. This is worrying, as it does little for the stability of West Asia. My answer is yes, we do need a new architecture – along the logic of ASEAN. We need a Middle East citizens’ assembly. We need a Helsinki process. We need to deal with the three clusters of the Helsinki process: basic security, but also human security; creating citizenship – something with which I have been involved for the last three years; and, of course, cooperation among states and societies in the region.

GB: Which countries would be critical or central to creating such a framework or process? How would you sequence potential membership outside of the central group of countries?

BT: I have always maintained that a cheap but compulsory admission ticket is required. Do you accept a comprehensive peace process – a true peace process – instead of a quartet when looking at the Israeli-Arab peace? Are we talking about Israeli-Palestinian peace, or a comprehensive Israeli-Arab or regional peace? We need an umbrella agreement for the region, and this umbrella agreement can ill afford to wait for perfect political settlements of sub-regional issues, including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or the question of the Iran nuclear programme. The umbrella agreement should address three very clear issues: first, security – weapons of mass destruction; second, anti-terrorism; and third and most important, human dignity.

Eighty percent of the refugees of this world are Muslims, and yet no concessionary fund whatever has yet emerged to this day in this part of the world. We are called upon as Muslims to create a universal zakat fund that would help put a smile on the faces of the followers of at least nine faiths with whom I have worked for six relentless years (and indeed on the faces of people of no faith at all). I have long been calling for a regional bank of reconstruction and development for West Asia – a bank to which all countries could commit on the basis of less sticky fingers – less corruption – and more good governance.

The cheapest compulsory admission ticket would mean that, with the P5+1 process as a point of reference, we would at least have a sounding board. We are talking about an organic, incremental, step-by-step approach. And the region’s non-Arab countries – Iran, Turkey and Israel – will also have to be brought on board, to be sure.

GB: Will the P5+1 process with Iran ultimately yield fruit?

BT: I hope that the Iranians and the West will step back from the abyss by June to come to an agreement over the future of weapons of mass destruction. If there is no progress soon, the talks may fail. Everybody is looking at the US elections in the fall and trying to position themselves. Consider Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech to the US Congress. It gives us great anxiety to think that our future in the region should perhaps be based on a bombastic speech by a head of government in front of Congress pointing to the need to attack Iranian targets.

There have been suggestions by the Iranian foreign minister that he intends to withdraw. What does such withdrawal mean? Does this mean that he is under pressure from his own extremists to go ahead and weaponize? What is missing in this whole equation is not debate about the alphabet soup of P5+1 alone or partners for peace or partners for the Mediterranean and all of these things, but instead to reflect on whether there is a serious and representative discussion group around these issues – putting their cards on the table, as it were, in the proper spirit, for that new architecture. Can we talk about a broader patriotism in this part of the world as a justification for helping the tens of millions of mobility and national stakeholders? Remember Churchill’s famous speech in Zurich, in 1946, when he called for a broader patriotism – so that one can at once be a European, a Bavarian, a German and a Catholic. Why can we not have a broader patriotism in this region – one where one can become an Arab of Jewish culture, or an Arab Assyrian or an Aleppan Orthodox citizen?

GB: What is citizenship in the Middle East or Western Asia today?

BT: For now, it is essentially flag-waving. Every pocket handkerchief state has a flag, a guard of honour, a seat at the UN, and so on. My late brother, who passed away some 16 years ago, once said: let us build this country and serve this nation. The nation to which he was referring was the Arab nation. If we have introduced Arabic into the UN as an official language, are we using the language responsibly, or is the Arab nation, with seven wars in six years, all too easily identified with Oriental despotism? (Of course, Oriental despotism in this world is not limited to Arab states.) The more I listen to comments by regional leaders, the more I believe that there are no civilized parameters for this West Asian region. You can say whatever you like in this part of the world and get away with it. The same does not apply to Southeast Asia, or even to South Asia – and certainly not to Europe or Eurasia. What does our region boil down to: a barrel of oil and a vast spending spree on new weapons to try out on our peoples? The legitimacy and defence of the nation cannot simply consist in the recourse to weapons.

Many of us once thought that the greatest disaster in our lives was the 1948 war, or indeed the 1967 war. But we have had a war in every single decade since. We have not, as a result, had the chance and time to evolve in a manner that is in keeping with my brother’s vision: improved quality of life, a meditative society, and so forth. There has not been a period of stability that has really given us that opportunity.

GB: What do you see as the near- and long-term future of the Israeli-Arab conflict?

BT: I am told by Israelis that there are some 10,000 front companies in the Gulf region alone – companies owned by members of the international Jewish diaspora. The members of this diaspora can hold whatever citizenship they like and not lose their ability to remain or become citizens of Israel. This allows them to conduct business in the Arab world unimpeded, even if Gulf countries have no formal diplomatic ties with Israel.

Still, it seems to me that the Israeli reality is that you have a wall, and that behind that wall you have an exclusivist, gated community – exclusivist even in the face of Sephardic or Oriental Jews, who are themselves worried about what the Jewishness of the state is going to mean. How does this Jewishness affect the Arabic language? After all, these Sephardic Jews – particularly the Iraqi and Moroccan Jews – are also the custodians of the Arabic language. So I think that the idea of the Jewishness of the Israeli state, and of a Jewish Israeli state that is primus inter pares in a regional patchwork of disorganized minorities, is worrying.

As such, I think that the solution to the conflict requires a regional model of citizenship – one that includes Arabs and non-Arabs alike, and one that will make economic and political opportunities for citizens in the region far more symmetrical and equal and just. There are many in Israel who support this vision. Indeed, I have discussed with some Israelis the possibility of a regional community based on water, energy and, to be sure, the human environment as a basis for stabilizing the regional order. This would be a win-win situation, instead of a zero-sum game.

GB: How would a regional security framework deal specifically with the question of weapons of mass destruction or nuclear weapons?

BT: Having served as a member of the Nuclear Threat Initiative board for 10 years, it seems to me that everyone can put their cards on the table. If you are talking about the Chinese versus Japanese situation over the Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands, for instance, then the conflict is actually territorial and identity-based. In our region, we have the question of Iran and its nuclear programme: does this ideological regime have the right to a nuclear capability for peaceful purposes? Does it have the right to weaponize? Of course, Israel believes that Iran does not have the right to weaponize because this would destroy Israel. The fact is, however, that such weapons and such weaponization would destroy me – that is, they would destroy everybody in this part of the world.

Let me add that I simply cannot understand why Pakistan and India cannot be a part of this discussion. They should be part of it. Is our region not a part of Asia? I do not see Asia or, for that matter, Europe consulting us on their security arrangements. Are we a black hole? No, we are a hugely important thoroughfare between Europe and Asia, and the regional architecture that we are discussing in this interview is a key part of bridging these continents in a way that respects our brute realities.

GB: Should Middle East countries other than Jordan ratify the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC)?

BT: I certainly think that if they are going to take international criminal justice seriously, then they should ratify. If they do not want to take it seriously, then do not ratify. Who has ratified to date in the region? The list is pitiful. Jordan, Tunisia and Palestine. Countries that have not ratified include Algeria, Morocco, Oman, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iraq and Iran. Israel, by the way, publicly stated that it no longer intends to ratify the treaty. How can we talk about the legal requirements for the poor if we do not respect the importance of empowering people through recognition of international legality as well as the shifting sands of national legality via some form of monitor? Some kind of an exchange of values based in law is necessary – particularly when it comes to women’s rights, children’s rights, and so forth. So I think yes, the more parties and countries that can be brought into a conversation on ethics, the better. I certainly hope that when His Holiness, the Pope, visits the US Congress this year in September – something that is unprecedented – and when he speaks to the UN, given the humanity that we have seen from his person, that he will touch on these issues. And I hope that other faith leaders will also take these issues seriously.

GB: What was the importance of the 2003 war in Iraq in some of the current crises in the region, including in the rise of ISIS?

BT: When attempting to stabilize Iraq by direct military action the US forsook some 400,000 members of the Iraqi military. To sack 400,000 people in the context of national economic depression and then to expect them to emerge as model citizens – particularly as new movements and militias are being created all the time – was evidently unwise. The Americans and Brits never asked themselves, really: how does this war end?

The split of Iraq into three parts – I do not wish to oversimplify – was self-fulfilling. But these three parts today still share a common concern over what will become of Baghdad. More generally, though, the episodes of violent fundamentalism that we have seen in the region over the last decade, sadly, do harken back to the basic question: what price do we owe Mesopotamia? I shall never forget an American soldier asking the director of a prominent European museum, “What is archeologically significant about Mesopotamia?” The answer was: “Everything.” But how can we call this region the Holy Land or the Levant if we continue to act on the basis of small-minded power plays rather than a broader understanding of strategy, and rather than developing a regional identity and regional institutions with equal opportunity for all?

GB: What caused the Saudis to not prop up the price of oil? And what effect has the collapse of oil prices had on Saudi Arabia, Iran and other countries in the region?

BT: I am not privy to Saudi or OPEC decision-making. However, for Iran and Russia, the fall of oil prices has evidently had a very sobering effect. Whether this dynamic causes less belligerence – say, in the context of the P5+1 or out of the Minsk 1.0 and 2.0 processes – is unclear. It is very difficult to come up with an exact calculus that allows you to conclude that if you depress prices to $50 or $40 a barrel, this is going to change the situation fundamentally – especially when people are living in extremely depressing situations anyway.

GB: What is your advice for Europe post-Charlie Hebdo? How should Europe and the West more generally react to terrorism?

BT: As I said, terrorism is by no means a new phenomenon. It is certainly not restricted to any particular groupings – despite the way that things are going in Islam and under the sobriquet ‘Islamist.’

I would say to the West that the time has come today to begin to consider a new international initiative – not only strengthening borders and security measures, but also recognizing the disappearance of multilateralism. If the West actually wishes to galvanize multilateralism, then it has to recognize that the League of Nations did not succeed partly because the US never ratified the Covenant of the League of Nations. If we want the new UN to succeed, then let us ratify those agreements that will set us on that incremental path of building a new architecture for the West Asia-North Africa region.

GB: Are you optimistic about the quality of young leaders being developed or emerging in the Middle East?

BT: I am optimistic that, after a very long period of darkness, the improvement of the situation in our part of the world is a common denominator between the 88 year old (take the new president of Tunisia) and the young people of the region. I think that what is important is to remind GB readers that leadership should not only be found at the political apex. Civil society matters. And there are signs of a movement in the Middle East that can perhaps one day produce a new social contract.

![]()

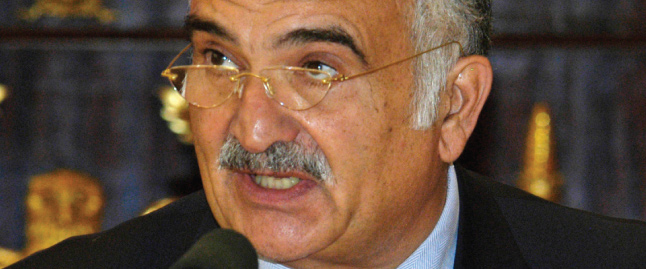

HRH Prince El Hassan bin Talal of Jordan is founder and chairman of the Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies (RIIFS) and co-founder and chairman of the Foundation for Interreligious and Intercultural Research and Dialogue (FIIRD).