“Future of violence with more women leaders…

Fatou Bensouda

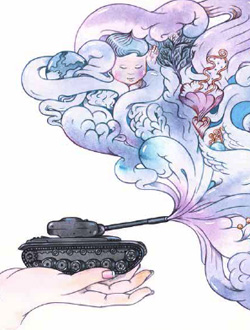

…depends on empowerment, which is what the issue of women leaders is really all about. As primary victims of violence within and outside of the home, as well as in the context of political and military conflicts around the world, women have a unique understanding of the psychological and physical impact that violence has on them, their children and society as a whole. Women leaders come with the innate characteristic of being nurturers, which gives a greater voice to another primary vulnerable group of victims of violence – children. Having more women leaders means increasing the representation of important groups of human society that have historically been marginalized and silenced. It means that a group that has rarely made decisions that have led to violence finally has a voice at the negotiating table. As a result of their experiences and qualities, women, as leaders, are uniquely placed to ensure that the thread that keeps the fabric of society together is strongly fastened. Women leaders have a critical and powerful perspective to bring to the table in leading the fight against violence.

It should also be said that human beings, regardless of gender, are born free and equal, and have both a great capacity to build peace and, alas, an aptitude to destroy. The litmus test is whether human societies – the world over – finally embrace and cultivate both sexes and afford them equal edification and opportunity. Doing so will create the nurturing environment that inevitably breeds the ‘constructive citizen’ – man and woman alike – who aims to build and positively contribute to the human experiment. More women leaders will precipitate this outcome.”

» Fatou Bensouda is the Prosecutor-Elect of the International Criminal Court (ICC), and the first woman elected to act in that capacity. Prior to that, she was the Deputy Prosecutor of the ICC, Solicitor-General, Attorney-General and Minister of Justice of Gambia.

Navanethem Pillay

…starts with the basic fact that women and men everywhere have challenged discrimination, and will continue to demand equality and human rights for all. We know that through equal participation and empowerment in all spheres, true transformation can happen. We know that even in times of crisis – or especially in times of crisis – capitalizing on women’s potential bears results. This is why, in echoing the voice from the streets of many cities, towns and villages around the world, we must insist upon structural and institutional changes: changes to ensure that women are recognized as equal citizens and equal partners in nation-building, and that all civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights are guaranteed for men and women everywhere.”

» Navanethem Pillay is the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, former President of the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and Judge of the ICC.

Danya Chaikel

…completely depends on who the women in power are. Certainly, women’s underrepresentation in high politics needs repairing. (Women make up less than 10 percent of world leaders. Globally, less than one in five members of parliament is a woman. The 30 percent critical mass mark for women’s representation in parliament has been reached or exceeded in only 28 countries.) However, the trouble with idealizing female leadership is that it fails to recognize the vast differences among women. A female in charge may just as easily embrace right-wing conservatism without any interest in social causes, as she may support a pro-feminist doctrine. On the other hand, a progressive man with a gendered approach to leadership will do more to challenge the established norms of international affairs than a traditionalist woman. Women display a range of leadership styles that depend on a multiplicity of characteristics intersecting with their womanhood. What about their religious upbringing, economic status, professional background, political party affiliation and legislative experience – to cite but a few potential explanatory factors?

A fresh approach to leadership is needed to address some of the inequalities that underpin today’s international affairs. This new model should first determine some universal international goals – such as the UN Millennium Development Goals – and then assess which leadership qualities can best bring about the objectives. In order for there to be real change in favour of women’s equality, ‘feminine’ qualities should be tested as potential virtues for good leadership. The opposite can be done for ‘masculine’ traits. Perhaps the findings will uncover that unyielding masculine leadership tends to bring on more armed conflicts – exacerbating poverty, violence against women and environmental destruction – as opposed to a softer approach, which may be more effective in bringing about, say, negotiated peace settlements through comprehensive multi-party discussions.

Rigid gender roles are already being broken down around the world, with some societies slowly accepting men who are taking on traditionally female roles in child-rearing and household work, and at the same time accepting that women can come out of the kitchen and actively participate in public life. This means that, in some corners of the world, male leaders can be more comfortable in exhibiting feminine characteristics, while women are more confidently expressing their masculine sides. The hope is that more of this gender-balancing can help in the reassessment of the qualities that make for a good leader. Such a rethink might then better bring about meaningful change to the traditional conduct and content of international affairs on issues affecting women in politics, economics, war and peace.”

» Danya Chaikel is Coordinator of the Forum for International Criminal Justice, International Association of Prosecutors.

Maryna Bilynska

…is promising. In principle, we might argue that violence is foreign to the core biology of women. At the level of the individual, the woman as ‘mother’ – or as the chief propagator of the human species – instinctually privileges the safety of the family unit – and children, in particular – and social and environmental stability in general. Inferior testosterone levels and, yes, superior stress tolerance together seem to militate against a woman being naturally inclined to fight wars, spill blood, dominate or kill, and instead make her favour the pursuit of peaceful means to solve disputes. For, in the end, she is always alive to the need for children to be born healthy, families to be fed and cared for, and the household to be protected.

Analogously, in high politics, a woman is unlikely to be a pure adventurist. Instead, the protective instinct animates her mentality and decision-making. She will always be open to dialogue both with foreign partners and different parties – friendly and less friendly – within her country. She thinks always of her duties to future generations.”

» Maryna Bilynska is Vice-President of the National Academy of Public Administration of Ukraine.