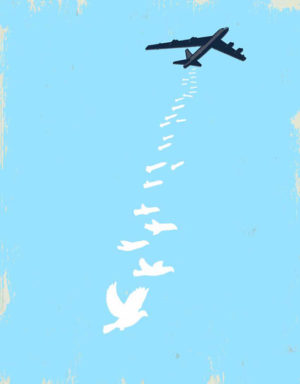

Between War & Peace

The last century teaches us that the purgatory between the perfect peace and total war is the strategic space in which the major deals of the twenty-first century will be crafted

The last century teaches us that the purgatory between the perfect peace and total war is the strategic space in which the major deals of the twenty-first century will be crafted

In a 1914 pamphlet, HG Wells declared that the First World War would pave the way for perpetual peace: “This, the greatest of all wars, is not just another war – it is the last war!… We face these horrors to make an end of them.” He was tragically wrong, of course, as were the scores of statesmen and diplomats who, over the course of the century, devised plans to make war an impossibility. Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations hardly lived up to its creator’s hopes. The 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, whose signatories solemnly promised to “renounce [war] as an instrument of national policy,” has long been a monument to either naïveté or cynicism, depending on one’s perspective. And, for all of its virtues, the UN has hardly lived up to its foundational promise to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war.”

The twentieth century’s catalogue of horrors tells us that diplomacy has limits. This is not to say that diplomacy has achieved no successes – quite the contrary – but it is essential to understand what it can and cannot do. It cannot solve all problems. Arbitration cannot resolve every dispute. Negotiating cannot end every conflict. And treaty-making cannot always build a desirable peace, because peace is not simply a matter of avoiding armed conflict. It requires more than just a treaty. This means that, in some circumstances, paradoxically, it makes sense to choose war over peace, and to fight to bring a more just and stable peace within reach.

What soldiers do on the battlefield constrains what diplomats can do at the conference table. At the 1945 Yalta summit, for instance, Franklin Roosevelt persuaded Joseph Stalin to sign the Declaration on Liberated Europe, which committed the Allies to building sovereign democratic governments in the countries emancipated from Nazi control. Stalin’s subsequent installation of a communist government in Poland fuelled accusations that, far from standing up for freedom, Roosevelt had in fact betrayed the Eastern Europeans at Yalta. But, regardless of Roosevelt’s intentions, no amount of diplomatic skill – indeed, nothing short of a new war – could have pushed the Red Army out of Eastern Europe. So long as Soviet troops were in place, Stalin had a free hand to do as he liked, and he knew it. In this respect, Yalta was not nearly as significant as its critics (most recently George W. Bush) claimed. When his foreign minister questioned the wisdom of signing the Declaration, Stalin replied: “We can fulfill it in our own way. What matters is the correlation of forces.”

A US-Soviet war over Poland in 1945 would have been the height of folly, but sometimes the wisest course of action is in fact to reject diplomacy and to keep fighting. Britain’s decision in May 1940 not to seek peace with Germany may be the century’s most important treaty that never happened. The Turkish rebellion against the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres offers another example of fighting for the sake of a better peace. Sèvres ended the war between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies, and proposed to cut the Empire into pieces. Furious at its terms, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk assembled a nationalist army to smash the treaty. His rapid, if bloody, success in the field forced the Allies to negotiate a new agreement, the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which kept Turkey – though not the Empire – intact.

But one must not conclude that it is always better to war-war than jaw-jaw. When he became US president, Richard Nixon was determined to end the Vietnam War, but only in a way that would not give the impression of defeat. A hasty retreat, he and Henry Kissinger reasoned, would only make the US look weak, and thus damage American security, which relied on the capacity to deter potential aggressors by projecting an image of strength. So even as they brought tens of thousands of American soldiers home, they expanded the war – for example, by bombing Cambodia and mining Haiphong harbour – in the hope not of winning, but of creating a position of strength from which to negotiate an end to the conflict. The chimera of credibility lured the US into a dangerous paradox: to preserve the appearance of power, it stuck to a policy that underscored its weakness. The 1973 Paris Peace Accords, which ended the war, kept Saigon’s government in place, and promised free elections, quickly evaporated two years later when a new Northern attack overwhelmed South Vietnam.

America’s engagement in Vietnam is a classic case of a war provoking domestic turmoil, but peace treaties can sometimes do the same thing. In 1905, after trouncing the Russians on land and at sea in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan won a favourable deal in the Treaty of Portsmouth, but did not get all of its original demands. When news of the agreement reached Tokyo, there was a riot. Thousands of people violently expressed their anger at the gulf between what the country had gained and what they believed it deserved. The consequences of the war were worse still for Russia, where the defeat contributed to a revolution that almost toppled the tsar. Fifteen years later, Ireland’s fight for independence demonstrated the risks of a backlash against efforts to establish peace. After several years of guerrilla warfare against British troops, Irish republicans signed a peace treaty with the British government in 1921. The Anglo-Irish Treaty established the Irish Free State, but only as an autonomous dominion within the British Empire – not a fully independent country. The compromises that the Irish representatives had made in order to reach a deal triggered a civil war, dividing the country between the treaty’s supporters and those who saw it as a betrayal of the republican cause.

Negotiating cannot end every conflict, and treaty-making cannot always build a desirable peace. In some circumstances, it makes sense to choose war over peace, and to fight to bring a more just and stable peace within reach.

As these cases suggest, diplomats need to remember that their actions can have unintended consequences. And the broader the agreement – the loftier its rhetoric – the harder it is to predict all of its effects. In framing the Treaty of Versailles in

1919, Woodrow Wilson championed national self-determination, a slippery idea in the best of circumstances. No advocate of racial equality, he meant it to apply to Europe, but not necessarily to the European empires. However, as historian Erez Manela’s recent book, The Wilsonian Moment, demonstrates, the subjects of those empires rejected this distinction and appropriated Wilson’s principles for themselves. The result was the growth of powerful nationalist movements in Africa and Asia. Even in Europe, Wilson’s idea created intractable problems, because it proved impossible to draw clear lines between allegedly separate peoples that often lived side by side.

Another agreement that took on a life of its own was the 1975 Helsinki Final Act. At the signing ceremony in the Finnish capital, none of the 35 assembled European and North American statesmen could have foreseen the Act’s far-reaching effects. Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev had originally demanded a pan-European agreement to ratify the continent’s post-war frontiers in order to entrench the status quo and thereby shore up Soviet power. Western leaders added their own desiderata to the agenda – notably provisions for the freer movement of people and information, as well as respect for human rights. In making these demands, they hoped to encourage liberalization in the Soviet bloc, but held out little hope of revolutionary change. Yet, over the fifteen years that followed, the Final Act’s human rights promises galvanized Eastern European dissident movements, which, in collaboration with Western governments and non-governmental organizations, played a major role in bringing down communism in Europe.

One of the Final Act’s key innovations was to recognize “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms” as a core principle of international security. Security was no longer a purely military question. It also required adherence to certain ideals – chief among them human rights. This was not a sudden shift, but rather a gradual trend that gathered steam in the 1960s and 1970s. Its traces are apparent in the history of the Nobel

Peace Prize, which was increasingly awarded to international human rights activists, such as René Cassin in 1968, Sean MacBride in 1974, Andrei Sakharov in 1975 and Amnesty International in 1977. In presenting Cassin with his prize, which recognized his role in drafting the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the chairwoman of the Nobel committee underscored the interconnection of peace and human rights. “What kind of peace,” she asked, “can there be in a country where the people are not free?”

Peace is more than just the absence of war. The corollary of this notion is that there exists a limbo between peace and war – where the fighting has ceased but freedon and stability have not yet taken root.

Peace is more than just the absence of war. The corollary of this notion is that there exists a limbo between peace and war – where the fighting has ceased, but freedom and stability have not yet taken root. Diplomats have to distinguish between a treaty, which silences the guns, and a durable settlement, which makes it possible for genuine peace to take hold. The persistence of instability after WW1 illustrates the difference. In 1919, the Allied statesmen in Paris tried to build a new international system that would hold Germany to account, solve the problem of the continent’s failed empires, and prevent another war. But as the 1920s and ‘30s proved, the Versailles system was anything but stable, despite fresh diplomatic efforts – most prominently, the 1925 Locarno Pact – to put international peace on a sounder footing. A similar pattern followed the end of WW2, though the ultimate outcome in this case was happier. Due to the Cold War, it took a quarter century to achieve a modus vivendi over Germany and Berlin, which had been chronic sources of crises in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. Nowhere is the distinction between peace and the absence of war more salient today than in the Middle East, where former enemies have signed treaties, but peace remains elusive. One might also look to Kosovo, which languishes in the twilight between peace and war, despite a decade of international reconstruction efforts.

Due especially to the rise of terrorism, the nature of war has changed over the last quarter century, and remains in flux. Will the nature of diplomacy and peacemaking have to change too? In the past, when major wars ended, it was possible to re-examine the international system’s governing principles. The rules of the road had to adapt to the new era. (Post-war windows of opportunities stay open only briefly, and, as the cliché goes, one should never waste a good crisis.) But whatever one calls the current worldwide conflict with radical Islamism – the ‘war on terror’ or something else – it is hard to imagine that it could conclude with anything resembling the Congress of Vienna or Paris Peace Conference. Politicians and diplomats are wrestling with the dilemma of whether it is possible or desirable to negotiate with non-state actors like Al Qaeda, Hezbollah and the Taliban, which play an increasingly important role in the international system. Just as the tradition of declaring war has declined, it may well be the case that traditional peacemaking – or at least the grand peace conference of the past – may be on the decline too. Over the coming decades, diplomats will have to grapple with the question of what should take its place.

Michael Cotey Morgan is a PhD candidate in international history at Yale University.

His work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal and The Globe and Mail, among other publications.