Reflections on the American Question

Will America survive this century? How can it channel its most brilliant qualities and suppress its worst pathologies? What has it still to teach the world, and what must it learn to learn?

Will America survive this century? How can it channel its most brilliant qualities and suppress its worst pathologies? What has it still to teach the world, and what must it learn to learn?

America is not a country. It is a civilization – without a doubt, the greatest of the great civilizations of the last two centuries.

I write this tract, humbly, not as an American proper, but as an outsider sitting at the edge of American civilization. I write as an admirer and beneficiary of American civilization – the son of Jackson-Vanik Jews from the Soviet Union, who has prospered (thus far) in upper North America on the original strength of American political energy, imagination, magnanimity and moxie. And I write in the full certainty that while this American civilization will endure for the balance of this new century (energy does not, after all, die; it merely changes forms), it is by now fully legitimate to wonder whether America the country – the USA – will do the same. And if so, what kind and quality of American country will this be?

Modern states last, on my calculation, about 60 years, after which they collapse or transform unrecognizably due to constitutional collapse and/or war. (The USSR, America’s great adversary in the last century, once fancied interminable and indestructible, lasted only 69 years.) If the American Civil War of the mid-19th century was the last major manifestation of American constitutional collapse, the American state that rose from the ashes of that calamity has, in more than a century and a half, with the small exception of the cross-border violence overflowing from the Mexican Revolution, known virtually no proper warfare on its continental territory. (Pearl Harbor was, evidently, very far from continental North America. I discuss 9/11 below.)

Show me a nation – almost any nation on Earth – that does not fancy itself more or less exceptional or distinct, and I shall show you a non-nation. The Chinese fancy themselves unique. So too with the Russians, the Jews, the Persians, the French and the Québécois of Canada.

This brings us quickly to the matter of America’s famous exceptionalism. Show me a nation – almost any nation on Earth – that does not fancy itself more or less exceptional or distinct, and I shall show you a non-nation. Tout court. The Chinese fancy themselves unique. So too with the Russians, the Jews, the Persians, the French and the Québécois of Canada. So what is the material differentiating fact of American exceptionalism (or the American belief in American exceptionalism)? Partial answer: the exceptional longevity of the modern American state, among all the states and political experiments or pilot projects that have come and gone, along with the country’s longstanding general exemption from war on the homeland.

Let us recall that, over the last century, almost every other country, on every continent – Asia, Europe, Africa, South America, and even Australia and Oceania – has endured and been transformed, painfully, by some description of brutal and sustained warfare on its territory. American exceptionalism today is therefore not only a political-constitutional self-identity (the inspired narrative construction of quasi-geniuses like Washington, Madison and Jefferson), but also a brute fact of international affairs and strategic history. In other words, American exceptionalism concerns not only the self-professed, ‘felt’ uniqueness of the American ‘idea,’ American institutions, American values and clear American success among the nations (to some extent, a ‘domestic’ or ‘internal’ question), but also, to be sure, America’s exceptional good fortune in having been essentially insulated, on the home front, from the world’s great catastrophes of armed conflict, even as this same America partook in – and sometimes, for good or ill, even initiated – such armed conflict. Of this good fortune, we can safely say that the relevant dimension of analysis is not domestic, constitutional or intra-American, but fundamentally international and strategic. (The 9/11 attacks, the national shock they generated, and the ‘biblical’ American response they precipitated, domestically and internationally, were the powerful non-state exception to the still apposite rule of American immunity – for now – from invasion and strategic tragedy on the home front.)

Let us take each of the domestic and international faces of the question at hand in turn.

The regular political and social experimentation that was at the very heart of America’s revolutionary project over the last two and a half centuries, built on an essential, competitive reengineering and reimagining of foreign practices – in government, in commerce, in jurisprudence, in the universities, in literature, in the arts, in sport and in matters of national strategy – has today found itself displaced increasingly by rigid dogma underpinned by resolute, earnest belief in the dogma.

America’s Domestic Proposition and Prospects

Perhaps the major internal paradox facing America today, in this early new century, is the fact that such a famously open society (a melting pot of the world, as it were) has become so intellectually closed. What is the nature of this national intellectual non-porousness? Answer: It consists in an abiding American incuriosity about the world and America’s comparative circumstances within it – even as America’s now acute internal political and social recriminations run rampant. Bref, the regular political and social experimentation that was at the very heart of America’s revolutionary project over the last two and a half centuries, built on an essential, competitive reengineering and reimagining of foreign practices – in government, in commerce, in jurisprudence, in the universities, in literature, in the arts, in sport and in matters of national strategy – has today found itself displaced increasingly by rigid dogma underpinned by resolute, earnest belief in the dogma. And even as America’s political tribes argue – ferociously, sometimes violently – among themselves over the details of that dogma, the American argument is today strictly domestic in interest, vocabulary and membership. On politics, policy, strategy, religion and on all other questions of what is ‘right,’ the larger carapace of American dogma remains oblivious to – and high underpenetrated by – the fast-changing outside.

Americans today would be surprised to learn that, among the Russians, the Chinese and the Americans themselves – the civilizational extensions, roughly, of the three great powers of our time – it is the Americans who are, by far, the most ideological. It is the Americans who really believe their stuff, as it were – increasingly, with little humour, humility or feel for irony.

The Russians today, for their part, believe in almost nothing. (Nay, if anything, the Russians often believe that the Americans are, all achievements considered, to be admired. If pressed, they would likely confess that they themselves wish to send their kids to Harvard and Yale, to live in Miami or Austin, and to work for Google.) Of course, I simplify to make the point, but only just. For Russia is, less than three decades out from the collapse of the USSR, a very young country still. The Russian national ideology, as with America in its earliest years of independence, is still being divined, moulded and legitimated. And like its leadership, the Russian political ideology – far more than the Russian mentality, perhaps – is eminently tactical and flexible, rather than strategic and consolidated.

In this flexible, ‘anomic’ post-Soviet ideology, the Russians maintain a reasonable sense of humour – not as rich, to be sure, as the Ukrainian sense of humour, but still alive to the tragicomedy of Russia’s precarious circumstances and uncertain fate, even in the coming few years. And armed with this flexible, still ill-formed ideology (tinged with the cynicism of lost belief from having seen a huge state and ideology collapse with great rapidity), today’s Russians have difficulty believing or taking seriously the possibility that the Americans could, even amid their fierce domestic disagreements, ever be so sincere, certain or pious in their beliefs – or, in other words, so unrelenting in their profession to ideological certainty and purity. And yet, this is indeed so. The Americans really believe. They are real believers.

The Chinese, while also admiring of Americans and America, are similarly incredulous of American ideological fixity. Contrary to Western thinking (and perhaps even Chinese realization), the Chinese today inhabit a young state – older than that of the Russians, but significantly younger than the US. And while China’s national ideology is considerably ‘thicker’ than that of post-Soviet Russia – the youngest of the three great powers – the country has, since the late 1970s and the Deng period, adopted a conspicuously and sincerely pragmatic character. Bref, the Chinese certainly still fancy themselves ancient and exceptional as Chinese, but they are merchants and deal-makers par excellence, which militates against purity and purism, and requires constant curiosity and learning about the circumstances of their opposite numbers around the world. And so the Chinese, for all the manifest pathologies of their current system, are always learning, everywhere and from everyone.

Woe betide, then, the true believers – the thick ideologues – for they do not learn very well. They are not open to learning. And regardless of the zeal of their belief (and America finds itself, surely, in a period of zealous belief – zealous macro-belief, as it were, among the zealots of America’s internal political camps), they will soon fall behind, or otherwise be left behind – perhaps without even realizing so before it is too late.

It is all the more problematic for the prospects of America that the constriction in American learning – as a society – should coincide with a manifest drop in the ‘performance’ of leading democracies in North America and Europe in delivering the ‘good life’ in institutional terms. The political radicalization of the two senior Anglo-American and indeed Western democracies – the US and the UK – as well as the weariness of the leading Continental European democracies in the face of populist challenges and practical failures on border security and mass migration, social cohesion, public safety, infrastructure, economic growth and employment, and the basic institutional connection between decision-makers and citizens, would all seem to commend serious pivots of posture toward greater national introspection and inquiry into the sources of their systemic weakness.

The correct response of a properly curious, porous society to these near-existential domestic problems (after all, can a government or system be deemed legitimate over the long run if it cannot solve basic problems of state and society?) should consist in both brutal self-examination and, to be sure, systematic external searches for best practices in addressing these problems. The unthinking society, by contrast, retreats to dogma, bombast and bark – at the margin, morality plays in which it – in the event, America – invariably plays the good guy on the ‘right side of history.’ (Show me, again, a nation that fancies itself on the wrong side of history, and I will show you a non-nation – or least a defeated one.) And this, alas, is where we find the essential American response to the country’s significant troubles of governance – both in process and outcomes.

The answer to the troubles of modern American democracy cannot be unreflective insistence on ‘more democracy.’ What if, as I note below, democracy, for all its virtues, has nothing to do with the problem at all? After all, democracy is but a system of government. And it is, as Churchill once noted, “the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” This appreciation of democracy is, of course, a stark departure from the strange present-day hagiography of democracy in the organization of men, as depicted in the contemporary American popular and official imagination; democracy as quasi-religion, as it were.

A cyber-attack by a foreign power on America during an election is seen not as a foreign strategic play – the analogue to America’s regular strategic interventions abroad – but instead as an ‘attack on American democracy’; an assault acquiring quasi-biblical character, as it were. Not only, on this logic, was America’s exceptional exemption from foreign assault breached, even if in the cyber realm, but so too was the religion of democracy – efficacious or not – molested. A national hysteria in respect of Russia and Trump-Russia ensued and persists, but with no visible curiosity about Russia itself or indeed anything of consequence outside of the immediate American hysteria.

But if the religion has not yielded the results of the gods, even if temporarily, then it must surely be the very notion of God that gets in the way of fixing the religion. In other words, it cannot be a puritan reaffirmation of democracy’s unique inviolability that overcomes the plain need to look at the comparative strengths (or at least problem-solving approaches) of other performing systems in the world – non-democratic and democratic alike – in order to address the weaknesses of American democracy in particular, and of the modern democratic order in general.

On this logic, I once asked a senior American dean of law how modern America, given its ills, planned – or planned to plan. He answered, glibly, “We don’t plan. Planning sounds very Soviet.” I answered that planning was human. All successful societies and organizations plan – if only to be able to do anything of consequence beyond tomorrow: build a school system, organize a cultural event, construct an airport or bridge, make a society sustainably safe, build an army or, yes, even a border wall. In the event, the dean’s response betrayed the victory of dogma over reflection, even within America’s most reflective classes. And this is a problem.

The revolutionary transformation of America’s media landscape, social and other media oblige, from the professional and institutional to the self-starting, increasingly amateur and self-promoting media class of the present day has only served to amplify the dogma and deepen the confusion about the fundamental systemic and intellectual weaknesses in American society, politics and policy – not to mention the major strategic mistakes and exposure I discuss in the second part of this meditation.

The mass, algorithmic weaponization and amplification of idiocy (nay, degeneracy) on Twitter and Facebook, multiplied by the serial, often sociopathic provocations of a president who tweets mostly to arouse and infuriate rather than to inform, teach and inspire, is today declaratively defended in America as democracy at work. And yet the growing perversion of the feedback loops to power that have historically been the great advantage of the democratic over the non-democratic world is seen very clearly only by the non-democratic world – a non-democratic world that is itself, paradoxically, constantly in search of such feedback loops (but not mass idiocy). Philosophical or official resistance to the anarchical free-for-all of this information space is glibly dismissed as necessarily autocratic – or, worse still, on the American understanding, fundamentally undemocratic. Said Victor Hugo, who himself, had he a Twitter account in his time, would have been debased, defamed, humiliated and ‘called out’ on any given day, on any given pretext, by the rabid caprices of the Twitterati who today masquerade as democratic warriors: «Souvent la foule trahit le people». (The mobs, even freedom-loving, can betray the people.)

In any other reasonable and thinking society – regardless of political system – this pathology (nay, psychopathy) would be tackled with the greatest possible seriousness. The capital mistake of system and society – the slaughter of children while they learn – would be corrected with maximum urgency and accountability.

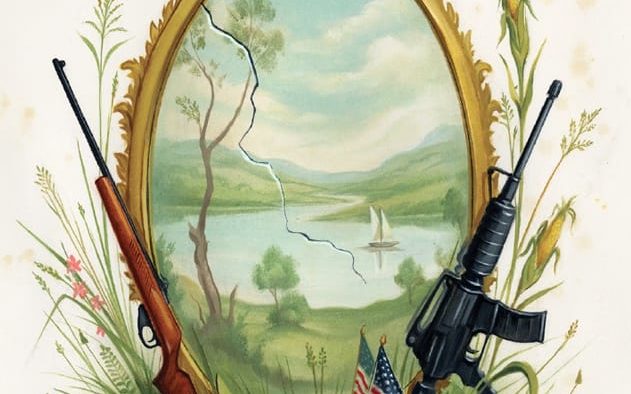

Daily gun massacres and regular mass shootings of children and young students in schools, colleges and universities across America over the last two decades – once unthinkable in the most advanced of Western societies – are today greeted with near shoulder-shrug by American political authorities. In any other reasonable and thinking society – regardless (I repeat) of political system – this pathology (nay, psychopathy) would be tackled with the greatest possible seriousness. In other words, the capital mistake of system and society – the slaughter of children while they learn, in the classroom – would be corrected with maximum urgency and accountability. If it should, God forbid, happen once – they would say – let it never happen again. Period. And heads would roll.

Not in today’s America. The massacres continue and intensify, in all corners of the country, with no national interest or credibility in correction. The perversion of the outcome – dead children and students in schools and universities – is earnestly defended by a good portion of the population, and by some intellectual elites, as the unfortunate consequence (an ancillary cost) of a fundamental democratic liberty (or democratic culture), namely the second amendment in respect of gun rights. (You want to live in our democracy? Then you will have to swallow the anxiety of sending your children to school, where they daily have to worry about being mowed down by bullets.) Of course, this curious conception of liberty only makes the outside observer crave a slightly less untrammelled version, if only to protect his or her children – as is done, again, in nearly all other developed (and most underdeveloped) societies on Earth.

The victory of dogma over reflection, and bark over introspection and self-correction is at its most perverse after the gun violence. The mass hysteria of the social media mob ‘reflecting’ American public opinion, armed with the fixity of its second amendment-cum-democratic liberty slogans, goes to town not only on those in America who would seek to remedy the manifestly mad, but even against the grieving father or mother, whose dignity in tears is ridiculed (even vilified) without mercy by the largely anonymous, sadistic hordes of online commentators placing themselves at the centre of a dystopian morality play in which each ensconces him or herself as protagonist. The tears of the mourning parents are but an instrument – at worst, a prop – in the self-dialogue of the American protagonist (always, of course, on the side of the angels).

And yet it is what I would call ‘the argument from parenting’ that is perhaps the best philosophical, moral and optical answer to the current American mania of gun massacres unaddressed by a mad hagiography of liberty – to wit, that the juxtaposition between the massive labour of love, time and money involved in raising a child (American or other) and the instantaneous swiftness with which he or she is allowed to die in a random gun attack in today’s US is a gross affront to the institutions of family, parenting and childhood, all of which are treated as holy in every civilized society in the world (and in America, no less, before the modern era of banalized massacres).

At the American border with Mexico, the very legitimate national prerogative to protect and police national borders and border flows – even fiercely – has been vitiated, grotesquely, by the theatrical sadism of separating families, often irreparably, and holding children in locked spaces for prolonged periods of time. There is, at the time of this writing, no obvious and serious American political interest in remedying this national obscenity, the character of which would easily be ascribed by American moralists to less democratic and therefore presumptively inferior political traditions.

Finally, there is the extremely apposite matter of the American president. I will not repeat some of the points made in my Open Letter to President Trump in the pages of GB two years ago. But, policy decisions and performance aside, the spectacle of a democratically elected American president whose daily behaviour contravenes so expressively every reasonable appreciation of political honesty, honour and class can only beg the question: What can America teach other societies today about proper governance? What can it teach other nations about civilized majority-minority relations? How can other countries and societies trust American leaders and American judgement when the country is headed by a commander-in-chief so craven in his deception? Which society, in any part of the world, would want its leaders to behave in such a manner? Answer: in truth, no society. Zero. For there is not a single leader in the world, democratic or not, who behaves like this today. And this means that very few societies and political systems will be pivoting to America – in earnest, with baited breath – for the foreseeable future.

Now, while this state of affairs does not foretell any necessary near-term collapse of the American political order, it certainly betrays the growing secular deterioration of the quality of this order. Collapse, of course, can happen fairly quickly, but American survival as a country in the absence of major correctives of leadership, policy and culture will be just that – survival as fact, but not as paragon or example, even if the people continue to believe.

***

American Foreign Interests, Mistakes and Responsibilities

Let me be clear, for the historical record. With some important exceptions, America’s international analysts today fail to impress. America still has, by far, some of the world’s best, most highly resourced and energetic universities, think tanks and publication platforms – on domestic and international issues alike. However, the mediocre standard of American analytics and frameworks in respect of key parts of the world not only lays the groundwork for future American mistakes of strategy (and explains past incompetence), but indeed conforms with the same deep-seated incuriosity, non-porousness and ideological fixity that have eroded the credibility of America’s domestic discourse.

On Russia, the apparent preoccupation – nay, obsession – of the American political class and media with that country since at least 2014 (the Ukrainian revolution and the Crimean annexation) and particularly after 2016 (the Russian intervention in the presidential election) would suggest some abiding American expertise on that huge country – in my view, the most complex in the world, and far more complex than America – and the post-Soviet space more generally. In the absence of deep expertise, one would think that America should be studying Russia, the Russian language and culture, and the very idiosyncratic dynamics of the post-Soviet space in some great depth and, yes, with curiosity – commensurate with the scale of the apparent assault on American democracy, and consistent with the sophistication of the target country. And yet American official, academic and media expertise on the subject remains exceedingly poor – paralyzed, to some extent, by morality plays and dated frameworks.

Little curiosity on Russia per se – as it is, in the guts, in all its colours and flaws – is on display in today’s America. Nay, the lion’s share of the Russia discourse is self-referential – a dialogue of hysterical intensity strictly among Americans about a country about which they know very little, and in which they are, sincerely, even less interested. A comparable but slightly less hysterical situation exists in respect of China – the newest target of American strategic speculation – to say nothing of Iran, North Korea and, before these, Iraq, Libya and Syria (to which I now turn).

Retrospective analysis of the catastrophic, American-led bombardment of Libya also commands little curiosity. And yet the deliberate decapitation of that country’s leadership through the killing of Muammar Gaddafi was patently unforgivable in both the strategic and moral realms of things. American analysis to this day appears to wonder aloud – sincerely – how anyone could possibly defend a person like Gaddafi in power. But this superficiality of calculus speaks to the entire edifice of American power today – capricious intervention by force covered by moral marketing (with America manifestly on the side of the angels and ‘standing with the people’ in the target country), net systemic destruction and destabilization, followed by a press for renewed use of force supported by a next-round moral sell. When pressed, invoke the liberal international order, in which apparently no other country or political tradition participated.

The death of Gaddafi led to the wholesale disintegration of Libya. From the outside, on the available evidence, it is not apparent that anyone in the American strategic apparatus (and definitely not in the political class) had anticipated or given serious weight to the prospect that, beyond the optics of killing a ‘bad guy,’ the crumbling of the Libyan government and state – the cork at the tip of Africa, as it were – would lead directly to the flooding of Europe by Middle Eastern and African migrants. By extension, no one in America today remembers or otherwise appears to care much about this sequence of historical events, and with it the genesis of some of America’s own anti-refugee radicalization under the leadership of the current president. This demographic flooding of Europe continues not only to kill tens of thousands of people yearly in the Mediterranean Sea, but also to strain significantly the relationships among the leading countries of the EU. And it has led, critically, to Brexit and the radicalization of the other great English-speaking democracy across the pond. As things stand, then, any future major American military incision into the Middle East – for instance, in Iran – could well lead to such massive refugee flows into Europe as to tear asunder the entire EU. Given that the EU is, by a long shot, the most important post-WW2 liberal international institution of them all, this would be a paradoxical historical contribution indeed.

The illegal American invasion of Iraq at the turn of this century led directly to the extreme counter-revolution of ISIS. The morality play created to fight that brutal force, having little already to do with the original moral marketing mobilized to remove Saddam Hussein, was completely oblivious to the central American role in its very provenance. When ISIS bumped up against Al-Assad in Syria, the overlap of two necessary morality plays for two unsavoury international actors only served to totalize the incoherence of America’s Middle Eastern interventions.

Under President Trump, this total incoherence, now extrapolated to most of the world’s theatres, has assumed a grotesque, absurd character – one almost too painful to describe for someone raised on a diet of American strategic literature that saw American foreign policy and American preferences at the heart of international strategic life.

What remains is that America is still a term-setting country on the global stage. This means, on the one hand, that every American action – wise or less wise – on the world stage continues to enjoy the essential capacity to mould the theatre of action in some consequential way, or to influence the effective rules or logic of the game.

What remains, however, is that America is still a term-setting country on the global stage. This means, on the one hand, that every American action – wise or less wise – on the world stage continues to enjoy the essential capacity to mould the theatre of action in some consequential way, or to influence the effective rules or logic of the game, as it were. American power may no longer be a sufficient condition for shaping many theatres – if it ever really was – but it remains necessary to the resolution (or, in the event of folly, further destabilization) of key problem areas internationally.

This term-setting American capacity is, first and foremost, a question of American mentality. Americans believe, with few complexes, that American action not only shapes reality – perhaps irresistibly – but indeed is reality itself. This is a formidable conviction of the national mind – one that, in competitive terms, can only leave in the American dust nations and peoples less bold or more circumspect. It is also supported, to be sure, by the still-remarkable American private-sector machinery comprising huge companies with global (extra-territorial) networks, massive and intricate webs of explicit and implicit support from venture capital and government, and a persistent, mythologized national respect for innovation, risk-taking and competition (and the very idea of competition).

Can America as a whole play this term-setting role appropriately and responsibly in the coming decades? That much is unclear. The US president – not just the current president, but indeed any US president of tomorrow or yesteryear, regardless of intellect and education – is by far the inferior of his or her counterparts in Russia and China in understanding the world and its moving parts. This is a plain fact. For each of the Russian and Chinese presidents governs a country with 14 land borders and multiple maritime borders – that is, each must be expert or regularly briefed (and therefore eventually expert) on the circumstances, cultures (mentalities) and interests of a good portion of the world immediately at his country’s edges.

The American president, even if armed with an Ivy League education, has little need of intimate knowledge of virtually any complex foreign country. He or she will typically need to have a basic apprehension of America’s border relationships with Canada and Mexico, but ‘felt’ understanding of most other foreign countries will be either discretionary or episodic – far from existential or essential. Presidential curiosity can only remedy the imbalance of ken so much; but presidential and system-wide incuriosity will assure that, in a crisis or under great pressure, America’s comparative performance will be poor.

Bref, the marriage of residual American term-setting capability with a new-century American society that is less and less curious about – and competent in analyzing – the world around it makes for a strange brew in the context of diminishing American power and some wicked new-century threats and dynamics right at America’s gates. Can America survive? Can it cope? For now, the American president – this one or all future ones – operates, internationally, just shy of the dyadic intersection of nuclear war (which the current president has threatened to initiate on several occasions) and a Nobel Prize (which even the current president could still win, and which speaks to the vast term-setting capability of American power and daring). Domestically, he sits at the apex of a colossal society that, while having mobilized huge forces of creativity and industry over the course of its distinguished history, could equally unleash a terrible energy of destruction and chaos, should it ever unwind, across all territories touched by American civilization.

We can be certain that, with China – geographically far closer to the US and continental North America than Washington or New York might imagine – returning to the strategic centrality and confidence it enjoyed before the Opium Wars that preceded the American Civil War in the 19th century, with the melting of the Arctic bringing Russia immediately to the borders of North America, and with today’s and tomorrow’s military and industrial technology making the US eminently ‘reachable’ – even by smaller powers, in the context of conventional warfare, asymmetric warfare and warfare by other means – there will be conflict on American soil in a foreseeable future.

Will America be clever enough to anticipate, avert or otherwise thwart (emerge victorious from) such conflict? That much, again, is not obvious at the time of this writing. The incurious bombast of present-day Americana does not bode well. Much will depend on whether the US is able to improve hugely its analytics and – as part of its capabilities – its strategic and political judgement. And if it does not, then America’s reaction, pre-emptive or retaliatory, to any surprising violation of its unique exemption from the world’s most terrible conflicts will be exceedingly ferocious – several orders of magnitude greater than the response to the discrete attacks of 2001.

Who knows what the world would look like the day after such a series of exchanges? What would America itself look like, if it were to survive at all? A curious possible end to the most brilliant and productive of modern countries would not be so shocking in the historical scheme of things… Of course, it could well be largely avoidable, in this same historical scheme of things…, if only this same country could bring itself to ask the right questions. Or to ask questions at all.

Irvin Studin is Editor-in-Chief & Publisher of Global Brief.