Ghana’s Energy Paralysis

Short-term pressures make any near-term African transition to renewable energy highly improbable

Short-term pressures make any near-term African transition to renewable energy highly improbable

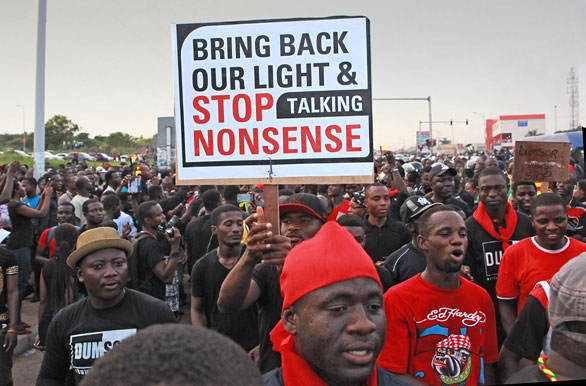

Africa is facing a deep energy crisis. From South Africa, across Central and East Africa, through Ghana and Nigeria, to the Horn of Africa, and even northward, industry and homes alike are often short of power. Ghana today has standing power requirements of about 5,000 megawatts. This includes some 2,500 megawatts of ‘suppressed demand’ – that is, people cutting down on power use in anticipation of shortages – as well as Ghanaian exports of power, dictated by national policy, to the country’s neighbours in the 14-country West African Power Pool. With total national generation capacity currently at close to 2,000 megawatts, power outages are frequent. Indeed, ‘dumsor,’ a Ghanaian term used to describe “persistent, irregular and unpredictable electric power outages,” has made it into Wikipedia.

Given that Ghana, like other African states, signed up to the climate change commitments in Paris late last year, Accra is now obliged to develop plans for national implementation. Ghana’s president, John Dramani Mahama, has also become co-chair of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Advocacy Group – with renewable energy now written into the SDGs. As such, Ghana must at least pretend to take a renewable or green energy agenda seriously, even as its basic energy needs are not being met. And, to be sure, outside donor funding – from the IMF, the World Bank, the UNDP, and various bilateral country donors – may well be impeded if demonstrable national action is not taken in the service of renewable energy.

Of course, what Ghanaian politicians and policy-makers actually do on a daily basis, in the context of four-year electoral cycles, with young, connected and impatient populations, is grapple with the country’s most pressing ‘micro’ issues – to wit, employment, budget deficits, and, doubtless, power at any cost. Long-term planning on issues relating to climate change and global warming, drought, famine and food security, disease and death are a luxury. Even if a number of long-term plans exist purely on paper, neither the political culture nor the policy mechanisms exist in Ghana for implementation of such plans. The result is superficial acquiescence to the long-term concerns, and aggressive action on short-term pressures like increasing the megawatts. To African leaders, then, making African economies work is the focus, while making them work cleanly is a distant fancy – with everyone fully aware that the quick energy fixes through diesel and coal displace the only sustainable type of energy (the renewable kind) and threaten to weaken the Ghanaian treasury if aid donors balk.

Twenty years ago, in many African countries including Ghana, the World Bank initiated a process of privatizing energy generation, transmission and distribution. Parastatals that were monopolies over all parts of the energy cycle were broken up and turned into limited liability companies. Although formally owned by the state, their legal constitutions, contracting and borrowing powers all became market-oriented.

Of course, in today’s Ghana, as in many parts of the world, the renewable and green energy movement is fast gaining momentum. The climate change work done under the aegis of the UN, alongside many other actors, has certainly revitalized this movement. The movement includes a strong non-profit and community element – a marked departure from the prior emphasis on power as a largely private sector concern. Ghana’s renewable energy law clearly recognizes these non-profit and community roles in developing renewable energy, stating: “Energy Commission shall […] create a platform for collaboration between government and the private sector and civil society for the promotion of renewable energy sources.”

Ghana’s lawmakers play on the differences in the various prescriptions and use creative legal drafting to ensure policy and operational paralysis in the renewable energy agenda.

However, the manifest contradictions between the older market-oriented policy prescriptions of the World Bank and the more recent renewable energy focus of the UN and the green movement more generally have put Ghana into a proper bind. Ghanaian policy-makers can ill afford to ignore any international institution, lest Accra become isolated from the international community and also lose out on billions of dollars in development assistance that it desperately needs to fund its current deficits. So what does Ghana do? Answer: its lawmakers play on the differences in the various prescriptions and use creative legal drafting to ensure policy and operational paralysis in the renewable energy agenda in order to meet more pressing energy imperatives.

Consider the transitional provisions of Ghana’s 2011 Renewable Energy Act. Article 53 of the transitional provisions reads: “Until such time that a Renewable Energy Authority is established, the Renewable Energy Directorate under the Ministry of Energy shall (a) oversee the implementation of renewable energy activities in the country; (b) execute renewable energy projects initiated by the State or in which the State has an interest; and (c) manage the assets in the renewable energy sector on behalf of the State.”

Embedded in these few lines is a major policy choice of the government – namely, an attempt to stifle renewable energy indefinitely. For one thing, the renewable energy law is not designed to be fully operational. The most critical agency for operationalizing the renewable energy law is the so-called Authority – a body vested with legal, regulatory, financial, administrative, operational and other powers to implement the law. However, by virtue of the said transitional provisions of the law, the Authority does not actually exist, and its functions are instead to be performed by “the Renewable Energy Directorate under the Ministry of Energy.” Of course, it was within the Ministry of Energy that the World Bank originally incubated its energy marketization agenda for Ghana. It follows that as long as this ministry is mandated to implement renewable energy, it will do so within a market model, which currently (and perhaps understandably) prioritizes ‘dirty’ over clean energy.

Clearly, the stereotype about African politics and policy-making as being unsophisticated is far from accurate. During the deliberations by Parliament on the provisions of this law, opposition member Kofi Addah, himself a past minister of energy, called for the establishment of a proper Renewable Energy Authority. The call was ignored. The result was an Act of Parliament that does not resemble the vast majority of Ghanaian Acts of Parliament. An Act of Parliament usually begins with the establishment of an authority, board or other agency, proceeds to empower that body, and then charges it with operationalizing a specific mandate. Instead, the Renewable Energy Act of Ghana begins with a number of pious stipulations, without providing for a specific institution that enjoys the relevant powers to implement those provisions. The Act creates a number of mandates and obligations, and proceeds to divide these among a number of competing institutions, including the Energy Commission, the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission and, among others, the Standards Authority. It is certainly not out of the ordinary to legislatively require collaboration between different public agencies in order to advance a particular policy objective, but it is neither common nor particularly wise to do so in the absence of a specified body that is mandated to coordinate all of these efforts in the service of real outcomes. It seems, then, that the Act was actually designed to lay the groundwork for major challenges to practical implementation from the outset.

The transitional provisions also guarantee that the renewable energy law will not be implemented anytime soon. In Ghana’s legislative style, matters that are intended to be operational at some definite point in the future are usually expressed as time-bound. For example, the national constitution provides for the establishment of critical national institutions such as the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice within six months of the coming into force of the constitution. And yet the Renewable Energy Act of Ghana specifies no timeline whatever for the establishment of the Authority. The result is predictable: five years since the Act came into force, there is still no Renewable Energy Authority in Ghana. Most recently, the new Ministry of Power (created in 2014), which now has authority for renewable energy, indicated that the processes for establishing the Authority are “ongoing” or “in the pipeline” – Ghanaian euphemisms, as it were, for things that should not be expected anytime soon. In the meantime, Ghana’s energy deficits are pushing Accra to broker deals with China and Brazil for coal-fired power. Bref, real-life political pressures are trumping any green or renewable energy programme.

Only the creation – indeed, the activation – of the Renewable Energy Authority that has been created in the Renewable Energy Act can move Ghana to credible action on clean, renewable energy. No amendments to the existing law are necessary. The Minister for Power can, administratively, simply create the Authority and transfer the powers now vested in the Renewable Energy Directorate in the Ministry of Energy to this Authority in his own ministry. (Note that Ghana’s last Minister of Power resigned – because of Ghana’s power misery – in late 2015. The acting Minister is John Abdulai Jinapor.)

To be sure, the Authority will require heroic leadership – and leadership that is able to lever international donor assistance and participation – to get anything done in the context of a political culture that is still not willing. But when it is finally created, it should get on with the work of implementing the provisions of the renewable energy law – not as a subsidiary mandate among other mandates, as in the case of the current Directorate, but as a primary mandate. That way, while the short-term focus of Ghana on dirty energy will necessarily continue, the Authority will at least give the country a fighting chance to deliver clean energy in the foreseeable future.

Raymond A. Atuguba teaches at the School of Law, University of Ghana, and is Team Leader of the Law and Development Associates (LADA) in Accra.