What’s the Future of Capricious War?

In North America and Europe, there is no war, and no prospect of war. In Asia, there is no war but very real prospects for war. Can anything be done?

In North America and Europe, there is no war, and no prospect of war. In Asia, there is no war but very real prospects for war. Can anything be done?

When the Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) was crafted at a diplomatic conference in Rome in 1998, it included provisions granting the Court jurisdiction over the crime of aggression (illegal wars). However, the issue was hotly contested. As a compromise, the Statute provided that the Court’s exercise of jurisdiction over aggression would be delayed until further provisions could be added – defining the crime and setting forth the conditions under which such jurisdiction could be triggered.

In 2010, representatives of the Court’s governing body, the Assembly of States Parties (the ASP), met at a Review Conference in Kampala, Uganda, where definitional and jurisdictional amendments were adopted by consensus – but not without strings attached. Only acts that constitute “manifest” violations of the UN Charter as to their combined “character, gravity and scale” are covered – leaving plenty of marge de manœuvre for argument as to relative egregiousness. Other than for cases referred to the Court by the UN Security Council, nationals of non-states parties will be altogether exempt from the Court’s aggression jurisdiction, as will be nationals of states parties that elect to opt out of such jurisdiction. Finally, the jurisdictional amendments cannot become legally effective until ratified by 30 states parties and reapproved by the ASP at some point after January 1st, 2017.

Assertions that aggression investigations initiated independently by the Prosecutor of the ICC or at the behest of referring states could be politicized are significantly undercut by the fact that nationals of states electing to remain outside of the reach of the Court’s aggression jurisdiction are completely shielded – other than where the Security Council refers potential aggression cases. In light of such limitations, the further delaying measures woven into the Kampala amendments smack of overkill.

Still, the Review Conference’s failure to immediately activate the Court’s aggression jurisdiction comes as no surprise. The permanent members of the Security Council – and a number of other states – have consistently expressed the view that it is for the Council to determine when an act of aggression has occurred. What is perhaps surprising is that, despite this, the amendment package managed to retain provisions that, if activated, could empower the Court – at least theoretically – to proceed with prosecutions for the crime of aggression even without the Council’s prior approval.

Past efforts to limit war-making may prove instructive. In 1928, many of the world’s major powers famously supported the Treaty for the Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy (the Kellogg-Briand Pact). The US Senate overwhelmingly approved the treaty by a vote of 85 to 1. The lone dissenter was John Blaine, a Republican from Wisconsin. He knew that the treaty failed to provide sanctions in the event of its breach, and that certain countries – including Britain and the US – had qualified their accession with declarations reserving the right to use force when, in their sole discretion, defence of their interests so required. He warned that, “weighted down” by such reservations, the treaty contained “the fertile soil for all the wars of the future.” He called it “a sham” because, without enforcement mechanisms, it was unable to deliver on its implied promise to outlaw war – an institution that he described as existing “because certain nations propose to dominate and bully the rest of the world.”

Kellogg-Briand’s shortcomings may well have been on the mind of Robert Jackson, Chief Counsel for the US at Nuremberg, when, just days after the judgement of the International Military Tribunal (IMT), he reported on the trial to President Truman. With obvious satisfaction at what he believed represented a ground-breaking legal precedent, he wrote: “No one can hereafter deny or fail to know that the principles on which the Nazi leaders are adjudged to forfeit their lives constitute law and law with a sanction.” He himself had forcefully articulated the beating heart of those principles in his opening statement to the IMT, declaring that “[t]he common sense of mankind demands that the law not stop with the prosecution of petty crimes by little men. It must also reach those men who possess themselves of great power and who make deliberate and concerted use of it to set in motion the evils which leave no home in the world untouched.” Submitting vanquished aggressors to the judgement of the law was, as Jackson so eloquently put it, “one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.”

The Nuremberg Principles were affirmed by the UN General Assembly in December 1946, and the blueprints for deterring aggression seemed to be on the drawing board. The Cold War, however, had a chilling effect on efforts to codify international criminal law. Progress was largely stifled for over a generation.

Following the Kampala Review Conference, efforts have been underway to achieve the requisite 30 ratifications of the aggression amendments as soon as possible – consistent with the conference’s resolve “to activate the Court’s jurisdiction over the crime of aggression as early as possible.” Regional ratification workshops have been held in New York, Strasbourg and Gaborone. Based on ratifications to date and pledges by dozens of countries, there is reason for optimism that activation of the Court’s aggression jurisdiction may soon be within striking distance.

Although the Court cannot yet exercise jurisdiction over the crime of aggression, it can exercise jurisdiction over crimes against humanity. Some have argued – particularly while aggression remains in legal limbo – that such jurisdiction should suffice to bring charges against those who initiate illegal uses of force that result in large-scale loss of civilian life.

In the final analysis, of course, the Court lacks enforcement mechanisms of its own, and depends on the cooperation of states in executing arrest warrants and facilitating meaningful investigation and prosecution. Certainly, any prosecution for the crime of aggression would present significant challenges – not the least of which may relate to accessing classified intelligence materials and sources. Still, such challenges are not unique to the crime of aggression: similar challenges are present when dealing with the other core crimes under the subject-matter jurisdiction of the Court. These challenges can be managed if the Court is adequately supported and equipped.

The ICC is complementary to national jurisdictions. This means that it is in national courts that cases are to be heard in the first instance, if possible. Consistent with this principle and with their obligation to cooperate with the Court, states parties should bring the Statute’s core crimes within their own criminal codes. It follows that in respect of the crime of aggression, domestic courts should be empowered to try their own nationals for commission of the crime. Beyond this, states generally have the right to try perpetrators of crimes committed on their territory – regardless of nationality. Of course, aggression is a leadership crime, and therefore head-of-state immunity might present an impediment to certain domestic prosecutions. By contrast, such immunity is not recognized by the ICC, which may, in the final analysis, offer a more suitable forum for aggression cases.

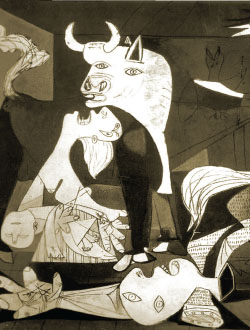

Ultimately, it may well be the court of public opinion that will be most influential in bringing the world closer to prohibiting the illegal use of force as a global norm. With the centenary of the commencement of WW1 approaching, and with ongoing violent conflicts prominently in the news, considerable attention continues to be focussed on the indiscriminate suffering that armed conflict invariably entails. Given humanity’s long history of organized killing, one might understandably question whether it is reasonable to expect the world community to suddenly take the steps necessary to hold to account those responsible for the illegal use of force. Indeed, it may well be that the wheels of justice, known for grinding slowly, may grind better when given a push.

Donald M. Ferencz is Visiting Professor at Middlesex University School of Law in London and the Convenor of the Global Institute for the Prevention of Aggression.