Guatemala Cannot Rebuild

The new century’s first successful intra-country genocide prosecution has been annulled. We start again…

The new century’s first successful intra-country genocide prosecution has been annulled. We start again…

Last March, an unprecedented legal saga opened in Guatemala: the trial of retired General Efrain Rios Montt and his former chief of intelligence, General Mauricio Rodriguez Sanchez, for genocide and crimes against humanity. This would be the first-ever genocide trial to be held in Guatemala, as the country struggled to assign legal responsibility for the 36-year long armed conflict that ended in December 1996. That conflict, between armed Marxist insurgents and the Guatemalan military, killed nearly 200,000 Guatemalans – the vast majority (upward of 80 percent), according to two post-war truth commissions, at the hands of their own government in a counterinsurgency campaign conducted in the early 1980s. This period is now known as La Violencia.

La Violencia hit its nadir between 1981 and 1983, when General Rios Montt served as both head of state and the de facto head of the Guatemalan army (the extent to which Rios Montt’s authority actually extended to the military and its actions was one of the key issues at trial). The violence struck particularly hard against Guatemala’s large Maya indigenous population – especially the Ixil Maya – men, women, and children who lived in a remote, mountainous area of the country where the guerrillas enjoyed support, and whom the Guatemalan military believed to be ‘100 percent communist.’ Although the legal parameters of the genocide case related strictly to the Guatemalan military’s scorched-earth campaign against the Ixiles in the early 1980s, Rios Montt was being tried both for having had command responsibility and, in the effective spirit of a show-trial, as a living symbol of the more comprehensive Guatemalan military Cold War project. (Although Rodriguez was a co-defendant, his low public profile in Guatemala made him very much an auxiliary to the case.)

Three key factors – absolute impunity for perpetrators of war crimes (mainly on the right, but also some on the left), the rapid rise in common crime, as a well as a concomitant decline in the rule of law (seen most recently in violent spillover from neighbouring Mexico’s narco-trafficking) – have left Guatemalans unable to move forward in rebuilding their country. The election of Guatemala’s current president, Otto Perez Molina, speaks to this paralysis. The motto of his successful 2011 campaign was the “mano dura,” or “iron fist” – part of a get-tough attitude toward crime in one of the world’s most violent countries (Guatemala’s murder rate is among the top ten in the world). The fact that Perez Molina is himself a former general who commanded troops for a time (he was then army major) in El Quiché – the state in which the Guatemalan army conducted well over 300 massacres during La Violencia – sent shudders through the human rights community when he assumed the country’s presidency in January 2012.

In the meantime, the clamour of genocide deniers continues to grow in Guatemala. These deniers are led by operatives on the political far-right, who continue to maintain that the Guatemalan military’s actions in the early 1980s were not genocidal, but rather necessary to save the nation from communist takeover. The right is also calling for the prosecution of former guerrilla leaders for acts of violence committed during the armed conflict.

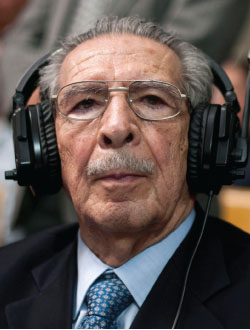

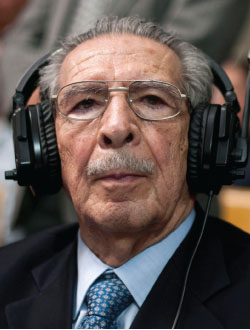

The Rios Montt trial riveted the Guatemalan public, who could scarcely believe the spectacle of the General on trial. (Rios Montt’s daughter, Zury, is today a powerful national politician.) At 86 years old, Rios Montt maintains his acuity and his military bearing. He remained expressionless through the various damning depositions of legal and human rights experts, and even throughout the testimonies of massacre survivors. In the trial’s first two weeks, some 120 Maya Ixiles told of rapes, the killings of family members, large groups of people in community centres set afire – all at the hands of the Guatemalan military. And forensic experts testified to the exhumation of no fewer than nine mass graves containing scores of people located just outside a single Ixil village.

About a month into the trial, things shifted dramatically – both inside and outside the courtroom. Dozens of Ixil Maya – many of whom had belonged to ‘self-defence patrols’ enlisted by the army to keep order during the armed conflict – were brought into the capital in buses draped with signs saying “there was no genocide” and decrying “hairy hippies and foreigners” (a reference to human rights observers). On April 18th, Rios Montt’s entire defence team, maladroit as it was, stormed out of the trial – leaving the General alone to face a formidable team of prosecutors. On April 19th, Yasmin Barrios, the young head of the three-person team of judges hearing the case, suspended the trial. The trial resumed on April 30th.

What of President Perez Molina, who had up to this point seemed rather aloof from the trial? At the trial’s opening, he too had expressed the opinion that there had been no genocide (“no hubo genocidio”). However, he had also said that he would not intervene in the case out of respect for the legal process.

A prosecution witness told the court that Perez Molina, in his previous capacity as military commander, had ordered the burning of Maya villages. Elsewhere, in Spain, where a similar case against Rios Montt is being built in absentia, sources say that there is also a mounting body of evidence against Perez Molina. In a recent interview, Perez Molina spoke of the Rios Montt trial as “a very emblematic case that has polarized Guatemalan society and revived the period of the armed conflict.”

There is no great cause for national optimism. In late April, the Guatemalan government ordered 3,500 troops into four indigenous communities. These were sent to establish ‘peace and stability’ because local people were protesting the opening of the Canadian-owned Escobal silver mine in San Rafael Las Flores – about an hour southeast of Guatemala City. Charging that organized crime groups – including the Mexican-based Zetas drug cartel (which has in recent years begun to operate freely in Guatemala, and against which Perez Molina has promised to take strong punitive action) – had duped local people into crime and violence, the government proclaimed, on May 2nd, 2013, a 30-day state of siege in four townships surrounding the mine.

On May 10th, the court sentenced Rios Montt to 50 years in prison for genocide, and 30 years for crimes against humanity – all told, an 80-year sentence for an 86-year old man. He was sent immediately to a military prison, where he was denied even the visitation of family members – including his brother, Mario Rios Montt, a retired former auxiliary bishop of Guatemala City. Rodriguez Sanchez, the other defendant, was absolved and released.

But General Rios Montt’s punishment was short-lived. On May 20th, Guatemala’s Constitutional Court overturned his conviction on a technicality. Lawyers for both sides say that the entire trial may have to be repeated. The appeal process could potentially go on for years. If one of the purposes of the trial was to allow Guatemala to move beyond its traumatic past, that goal remains elusive.

Virginia Garrard-Burnett is Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She is author of, among other books, Terror in the Land of the Holy Spirit: Guatemala Under General Efrain Rios Montt, 1982-1983.