Indigenous Canada and Canada’s Adaptation Imperative

Adaptation is a consistent theme in the various meetings of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to discuss climate change and what the world’s governments are prepared to do to address this issue. The UN website is clear: “Climate change is here. Beyond doing everything we can to cut emissions and slow the pace of global warming, we must adapt to climate consequences so we can protect ourselves and our communities.” The logic is clear. Climate change is here. We cannot deny the changing planet, and those changes are going to cause disruption to human societies. Therefore, we must adapt to minimize the disruption that is a necessary consequence of our past behaviour in respect of carbon emissions.

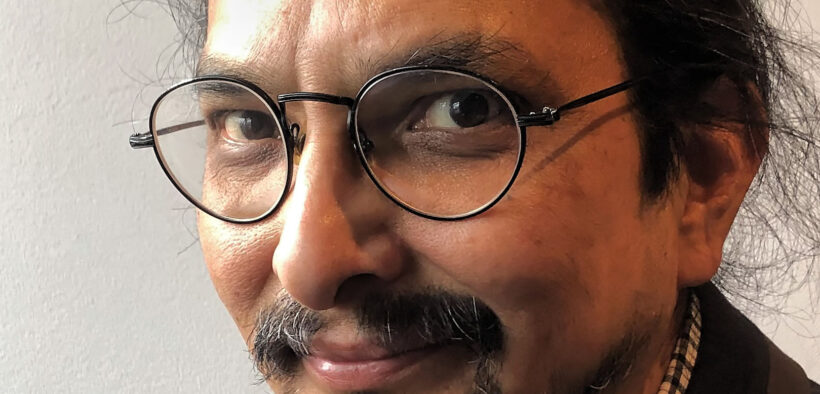

I had a chance, recently, to think about the history of my own family, and that of my Indigenous brothers and sisters more broadly. Until being taken to residential school, my mother and her parents and siblings spent their winters on a trap line: moving trap to trap along a predetermined route, setting and resetting traps, skinning fur for cash sale, and meat for the stew pot. As for her son – me – I am a professor of law at a prestigious Canadian university, and this is a change that my family made in just two generations. Sometimes it is said that we Indigenous people survived, or progressed, but neither of those captures what actually happened. We did not just survive. We did not ‘make progress’. Rather, we Indigenous people adapted to changing circumstances, and to the massive disruption of our Indigenous societies.

Sometimes it is said that we Indigenous people survived, or progressed, but neither of those captures what actually happened. We did not just survive. We did not ‘make progress’. Rather, we Indigenous people adapted to changing circumstances, and to the massive disruption of our Indigenous societies.

In their oral histories, the Mi’kmaq people tell a story about the coming of the last ice age 10,000 years ago, their people’s long journey south ahead of advancing ice sheets, and then their slow return north to their much changed, though recognizable, traditional territories. Indigenous people have adapted to climate change. The experience of massive earthquakes taught Indigenous people on the west coast to look for signs of tsunami, and to locate villages well outside vulnerable lowlands. These are impressive signs of cultural ingenuity and knowledge.

But still more impressive is the adaptation of contemporary Indigenous people to the massive physical, political, economic, social, ecological and philosophical upheaval since the arrival of European settlers. In some places, like in my own family, much of that adaptation has happened in as little as one or two generations. It is remarkable, though it begs a question: Why has Canada, and why have Canadians more broadly, failed to adapt to the reality that their relationship with Indigenous people is broken, unjust, unfair and unequal?

Why has Canada, and why have Canadians more broadly, failed to adapt to the reality that their relationship with Indigenous people is broken, unjust, unfair and unequal?

In recent years, it has become a cultural touchstone to claim that “we are all treaty people.” This phrase, first given voice by the Anishinaabe scholar John Borrows, was, in its original context, designed to point out that the historical treaty regime were agreements between two parties: Indigenous people and the settler Crown governments. By stating that ‘we are all treaty people’, Professor Borrows was drawing attention to the fact that non-Indigenous Canadians are also parties to the treaties. In recent years, however, it has become increasingly clear that settler Canadians are virtually the only beneficiaries of the historic treaties – while Indigenous partners are left poor, on tiny reservations, with little chance for meaningful economic development, and exceedingly high levels of unemployment, incarceration, and ill health.

Yet despite these inequalities, we Indigenous people continue to adapt. There is now an Inuk governor general, and an Abenaki justice on the Supreme Court of Canada – this despite the many economic and social challenges of Indigenous life in contemporary Canada.

Canada, and Canadians in general, have, on the other hand, been conspicuously slow in adapting to the reality of life in a nation historically and constitutionally bound together not by two, but three, founding partners.

French Canada has, since Confederation, enjoyed considerable legislative authority over the territory of Quebec, and English Canada has identical authorities in the rest of Canada. Meanwhile, Indigenous Canada has languished under the thumb of federal and provincial governments. Quebec wants more political authority to be able to organize a uniquely French Canada. And this is exactly the same set of concerns raised by Indigenous Canadians – though, to be fair, often in the less precise formulation: land back.

Quebec wants more political authority to be able to organize a uniquely French Canada. And this is exactly the same set of concerns raised by Indigenous Canadians – though, to be fair, often in the less precise formulation: land back.

Land is not really the thing. What Indigenous people need settler Canada to understand is that real change is only possible when we recognize that the issues that we face are political – not legal or historical. Canada can adapt to the reality of Indigenous Canada by thinking about its relationship with Indigenous people as a set of essentially political questions: Who has authority to govern Indigenous traditional territories? What does it mean to be in a relationship of treaty equals? What is a just distribution of power and wealth? And how can that distribution be justified?

These are, of course, big questions, but they are the linguistic and political terrain that we must traverse in order to adapt to the reality of Indigenous Canada.