Reconciliation in Canada: Changing Both Narrative and Policy

In recent years, many Canadians have given thought to what reconciliation between Indigenous and settler peoples might mean. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) made 94 calls to action, directed at Canadian institutions of all kinds. Even if you had never heard of the TRC, you could not help but have noticed the now-standard Canadian opening to every public event, large or small – namely the Land Acknowledgement, where an event’s organizer publicly recognizes that the event is taking place on the traditional territory of this or that Indigenous nation.

Various bodies are tracking progress on the Calls to Action, but most agree that we are about halfway down the list. And while I strongly suspect that my settler neighbours have noticed, it is most definitely the case that we Indigenous Canadians have noticed that nothing has really changed. There is still widespread inequality. Indigenous people do not own any more land, or have any greater control over their lives, or feel any better off than before all of this reconciliation stuff began. Indigenous people remain, in the statistician’s tongue, ‘overrepresented’ in patterns of arrest and imprisonment, in matters of child poverty, foster care and defection or ouster from schooling, and ‘underrepresented’ in the judiciary, corporate board rooms and university classrooms.

Indigenous people remain, in the statistician’s tongue, ‘overrepresented’ in patterns of arrest and imprisonment, in matters of child poverty, foster care and defection or ouster from schooling, and ‘underrepresented’ in the judiciary, corporate board rooms and university classrooms.

At the same time, Canadians are widely ignorant of their own history. This, in turn, means that the inequalities endured by Indigenous people are witnessed without context, and those inequalities become explanations. “They’re poor because they’re Indians.”

“They’re poor because they’re Indians.”

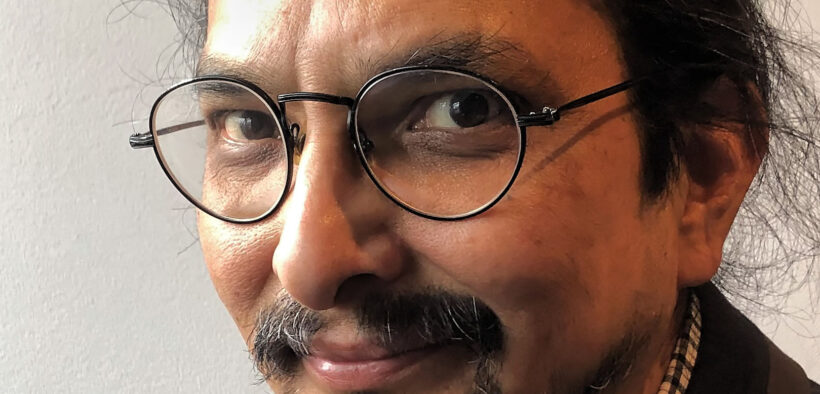

In a recent book that I co-authored with Andrew Stobo Sniderman, we take up these issues – not just as policy, but as narrative. Valley of the Birdtail follows two families, one Ukrainian-Canadian and one Ojibway, living in neighbouring towns for more than 150 years. We show how the federal government’s ‘Indian policy’ reduced one family to poverty and virtual imprisonment on the reservation, and we show how laws still hobble economic development on Indian reserves today. And while Valley of the Birdtail does journey through the nightmare that was the Indian residential school system, we go further. We continue to follow the story as government after government, mandate after mandate, chose to give Indian children less when it came to education.

To be fair to the current Liberal federal government, Prime Minister Trudeau’s commitment to match provincial education funding on Indian reserves has largely been met. But the current government’s commitments can be eroded, and let’s face it, will eventually be eroded, as government priorities shift, and as politicians are reminded that Indigenous voters are too few to be of consequence at the polls. Moreover, it certainly does not help that Indian reserves are largely never seen by settler Canadians – so whatever ugliness such policy choices might breed, will be far away and largely out of sight, as they have been since Confederation.

Valley of the Birdtail provides readers with a combination of historical context and new policy options to create a more equal Canada. But we are not dreamers. We were both political staffers. We know that a change in policy always means that some people are better off, while some are made worse off. So the smart move is, as was put so eloquently by a colleague, to deal with losers at the outset. There is a cost to be borne by settler Canada, but we argue that Canada has a unique set of tools and political conceptions that make more equal outcomes possible. For example, Canada already has two languages, and two distinct legal traditions; we already understand our federal system as meaning that we can be subject to overlapping orders of governance; and we have a constitutionalized system of equalization that could be harnessed precisely for the formula’s purpose: to even out winners and losers in a shared federal structure.

We know that a change in policy always means that some people are better off, while some are made worse off. So the smart move is, as was put so eloquently by a colleague, to deal with losers at the outset.

Valley of the Birdtail reimagines these institutional pieces, and provides readers with the historical context to see that in this vast nation, there is enough to share, and reconciliation is possible.