On Australia’s Fires, China and American Angst

Just a small taste of GB’s upcoming issue. Subscribe online today.

Enjoy your Brief!

GB: Can you describe the current situation in Australia? What has been happening over the last few months? Where are things headed?

GE: Australia has been experiencing some really catastrophic climatic events, including massive bushfires that have been unprecedented in their scale and intensity. These events have had very serious economic and ecological impacts on the country. They have also been accompanied, unhappily, by a degree of denial on the part of our government about climate change having much to do with any of this. Along with this, we are experiencing a pretty obvious mood change in the Australian public. Politically, the government’s stock has fallen quite dramatically. The prime minister’s personal stock has fallen dramatically. So, the country is at a really interesting pivotal point.

GB: What is your understanding of what caused the bushfires, or indeed the scale of bushfires this year?

GE: It is a combination of climatic conditions. Last year was the hottest on record for Australia . The country had dried out. It was absolutely tinder-dry prior to the outbreak of the fires. There have been some idiosyncratic meteorological developments in the Indian Ocean, pressure zones and so on, that have generated higher winds than usual. Overwhelmingly, the fires originated from natural causes, such as lightning. There is some disposition, in some corners, to suggest that it is all the result of arsonists and bad practice – say, of not backburning in preparation for the fire season. Essentially, though, Australia saw a number of largely natural factors coming together to produce a sort of physical holocaust. It has really been quite extraordinary to experience.

We recognize that this is a major change occurring worldwide, of which we are just one of the disbeneficiaries. We also acknowledge that any policy change that we bring to the international table is going to have a marginal impact. However, Australia has traditionally exercised a significant leadership role on multilateral policy issues, and the abdication of that role has been one of the things that has distressed me most about Australia’s positioning in recent years.

GB: Is there a sense that this is becoming the new normal for Australia – that is, that these fires will acquire an annual, cyclical quality?

GE: Absolutely. Of course, we recognize that this is a major change occurring worldwide, of which we are just one of the disbeneficiaries. We also acknowledge that any policy change that we bring to the international table is going to have a marginal impact. However, Australia has traditionally exercised a significant leadership role on multilateral policy issues, and the abdication of that role has been one of the things that has distressed me most about Australia’s positioning in recent years.

Climate change is real. Evidently, bushfires have multiple causes, and climate is only one factor among many. But there is a recognition that there is really something quite fundamental going on here, and that the world must get its cooperative act together very, very quickly if we are going to avoid the situation becoming even worse over the long haul.

GB: Is there anything that Australia could have conceivably done to prevent or dampen the magnitude of this year’s fires?

GE: The experts tend to say no. There has been a huge amount of effective action on the ground. The loss of human life has been actually very low compared to the past. Given the extraordinary scale of physical and natural damage – including to animal life – loss of human life has been very low because very stringent and effective evacuation and rescue procedures have been in place. All of this has been done about as well as possible.

To be sure, there are questions as to whether there could be more backburning during the off-season in order to create fire breaks. But most of the experts are saying that no, there was not a realistic option to do this, given the amount of vegetation and the dryness of the country through our winter period. In short, we are caught in a natural development. What we have to do is recognize this and also that, as part of a larger global phenomenon, we have got to play our part in addressing it.

GB: What can Australia do? What is Australia’s strategy for next year and for years after? What would you do to improve the situation?

GE: The Australian government has accepted only the most minimal of obligations on Kyoto and subsequent agreements, and has not covered itself in any glory in the more recent Madrid and other conferences. It has tried to take advantage of every conceivable technical loophole – including credit for past behaviours – in order to minimize the kind of response that we are prepared to make. There is a strong sentiment developing in the population as a whole that Australia simply has to sign up to more stringent emissions targets, and also assume far more stringent policy positions domestically than simply putting some government support into renewables. This has become an absolutely central issue in Australian politics.

The Australian government is still, for the moment, in denial about this. My own view is that the impact of these fires, the scale of the devastation and the scale of the risk that we are obviously going to continue to face in the years ahead, have together led to a quite fundamental stiffening of the sentiment on this issue in the Australian community. The government will ignore this sentiment at its peril. I fully expect, over the next few months, significant modifications in Canberra’s international position, brought about by domestic political pressure. As I have noted, the opinion polls are already showing significant decline in support for the government since the fires erupted, and a very material decline of about eight percent in the prime minister’s personal support. Whether this decline will continue once the immediate threats subside remains to be seen.

But this is a very real development. Public sentiment on issues does change – we have seen it in Australia on issues as fundamental to the psyche as gay marriage, among others. When an issue bites in the wider community, it really does bite. And governments ignore that change in sentiment at their peril.

GB: Is your submission that the main strategy for Australia is to become an international leader to push the international agenda, or international performance more generally? There is not a conspicuously local climate change phenomenon that Australia can fight – that is, the effort would have to be global. Is that correct?

GE: Of course, it must be global. We are dealing with a global phenomenon here. Australia is only a very small player in the larger global scene. But in per-capita terms, we are among the leading global emitters of carbon dioxide. Australia, traditionally, like Canada, has played a very creative and significant leadership role in mobilizing international coalitions around global and regional public goods issues. We have done that in the past in multiple areas, including arms control. But we have gone missing in recent years, and we can and should do it again. When Australia goes missing in international fora, it is significant because we do have a track record of energetic, creative and activist policy advocacy. We have a tradition of being the leader, not the follower, on these issues, rather like Canada – not during the Harper years, but certainly over a longer historical period. Australia really does have a role to play that is above and beyond the percentage contribution we are making to the global carbon emissions problem.

GB: What is your assessment of Australia’s current posture vis-à-vis China?

GE: For years, we have been saying that we need to position ourselves so that we do not have to choose between China as our primary economic partner and the US as our primary security partner. That is still the case. Both sides in Australian politics continue to take that position. And yet it is clearly becoming harder to navigate a reality that features growing Chinese assertiveness and growing American impotence on obvious policy issues. All of this will require some hard choices to be made by Australia.

The issue of Chinese influence – that is, of Beijing seeking influence in Australia – is, to some extent, exaggerated and overstated. Still, it is a real phenomenon against which we do have to guard. There is bipartisan support in Australia for quite strong legislation that has been passed in the last year or so to address the question of foreign influence through political party donations or other forms. There is manifest national concern to ensure that foreign investment policy reflects security concerns about possible excessive Chinese influence that puts various sectors at risk.

The mood in Australia, which I share, is that we do have to protect our own national interests in these areas. But we should do it in a way that is sensitive and does not overreact. Let us not demonize the 1.2 million Australians of Chinese origin (who are a fantastic national resource), and let us not put at risk the overall economic relationship with China – a relationship that is so critical to our future. This is a difficult course to navigate.

It does mean that we not only have to be loud and clear in our response to questions arising about excessive Chinese influence – through cyber activity or more traditional forms of influence-seeking – but also appropriately reactive to overassertiveness by China in the larger region, the South China Sea and other theatres. We should not just accept that as a necessary reality, but instead join others in pushing back against it. It means that we have to be true to ourselves on universal human rights issues, and call out major violations when we see them – in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong or elsewhere – and take the risks necessarily involved in so doing. In being true to ourselves, we need to line up some barriers.

At the same time, this is a matter of finding ways of engaging with China on areas of potential common ground. To this end, there is a very large multilateral agenda that could be much more actively pursued by Australia with Chinese interlocutors. On climate change, for instance, China has emerged to fill the gap left by the abdication of American responsibility over Paris. On international peacekeeping, China has been a very responsible and effective player. There is also potential on arms control – including nuclear arms control – where it is not to be assumed that China is a lost cause, but rather that it can be a very strong voice in restoring sanity into the nuclear disarmament issue (even if Australia is itself a very small player in that space).

There are other global and regional public goods issues, including pandemics, counter-terrorism, counter-piracy and population flows, where there is potential for very active cooperation with China. There is definitely not enough debate in Australia about those possibilities. But when you are in a stressful situation with a country, you need to look for areas of positive engagement.

The larger issue for Australia is how we cope not just with China’s new assertiveness but indeed, simultaneously, with a significant decline in American commitments to the region, and with serious doubts emerging about the reality of American security protection vis-à-vis Australia.

The US is the other side of the China coin. We cannot talk about China without talking about the US. That is a balancing act in which we are all engaged. The larger issue for Australia is how we cope not just with China’s new assertiveness but indeed, simultaneously, with a significant decline in American commitments to the region, and with serious doubts emerging about the reality of American security protection vis-à-vis Australia.

A couple more things about China. One is that there has been a very notable turn in Australian sentiment, as evidenced by a recent Lowy Institute poll. That poll, taken toward the end of last year, shows a 20 percent drop in the Australian public’s confidence in China to act responsibly on the world stage. It was up at around 52 percent in 2018, but it is now at 32 percent. That is a function, I suppose, of a year of really quite intense, adverse publicity about influence issues. So that is a difficult backdrop. Second, an interesting counterpoint to that drop in sentiment is that when it comes to confidence in world leaders, there is still, among Australians, more confidence or trust in Xi Jinping’s capacity and willingness to act responsibly than there is in that of Donald Trump. Indeed, Donald Trump only out-polls Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un – both at the bottom of the pile. That is why I say that for all the angst about China, we have got to look at this in a larger environment.

GB: What is your assessment of China’s performance in dealing with the coronavirus emergency? What do you make of Australia’s reaction?

GE: The most that I can say right now, based on the evidence thus far, is that there is room to argue that China initially underreacted to the crisis, and that Australia and the West have overreacted. But the jury is still out.

GB: How do you see the possible futures of China as such over the next five years?

GE: I am not one of those who is skeptical about the Chinese economy or believes that it is inexorably headed into decline. There are evidently stresses with which China has to deal, and there are also obvious internal political stresses associated with Xi Jinping’s dominance and whether that can be sustained at the present level. Essentially, though, I think that we are going see more of the same from China – through a whole range of external activities, including the Belt and Road Initiative and activist policy in the South China Sea. We are not going to see any stepping back on the part of Beijing in terms of exercising or trying to establish its weight as a regional player – militarily, politically, economically and also globally as a rule-maker rather than just a rule-taker. I do not see any change in direction or impetus. What I do see, however, is a degree of caution on the part of the Chinese authorities about pushing any of this to the point of actual physical, kinetic conflict. The Chinese are extremely keen to avoid that. They will, very happily, try to push the envelope as far as they comfortably can. But when they are confronted with serious pushback, we will see, as always with China in the past, a willingness to step back, take the longer view, and not push things to the point of actual confrontation.

As such, it is very important that countries like Australia work cooperatively with other important regional players like Indonesia, India, Vietnam, South Korea and Japan. These are the big five partner countries for us in this context.

GB: What about Singapore?

GE: Singapore punches above its weight in terms of military capability, but it is a country of about six million people. I am talking about the really major players. Singapore and Malaysia are traditional partners in all sorts of things with Australia. Thailand is less obviously so at the moment, and the Philippines also less obviously so because of its domestic politics. My view is that the sensible policy for Australia would be to work not so much at building formal alliances here, but rather at pursuing close diplomatic and military cooperation and close understanding of our common interests such that China gets the message that any form of overreach will not be ignored and will not be comfortable for it.

My overall take on how Australia should be reacting to these multiple developments and others that we have been talking about is summarized in the mantra: less United States; more self-reliance; more Asia; and more global engagement.

We are already seeing such an outcome with Indonesian pushback on fisheries in the South China Sea. We are seeing it in terms of warming Australian bilateral relationships with both Vietnam and India. The Australian government is doing many things with which I disagree, but I believe that it does ‘get it’ about the necessity to work very hard on building these other relationships. My overall take on how Australia should be reacting to these multiple developments and others that we have been talking about is summarized in the mantra: less United States; more self-reliance; more Asia; and more global engagement.

By less US, I do not mean walking away from the US alliance. But I do mean having a healthier sense of objectivity about where America is now at in terms of its effective capacity and willingness to play the role of regional and global leader. As I have often said, “Wherever thou goest, I will go” might be good theology but it does not make much sense for countries with a healthy sense of their own independence and a need to develop effective capacities to deal with multiple contingencies in this new environment. And by ‘more self-reliance,’ I evidently mean recognition of the possible worsening of the military situation over time. I do not envisage any overt move toward confrontation from China or anyone else. I can definitely see it in the future, but clearly the capabilities and the realities are changing, quite dramatically, and we always have to deal with capability, rather than known or currently believed intent. Australia has really got to be prepared to be spending more on its own defence than it has in the past.

By ‘more Asia,’ I am, for all practical intents and purposes, referring to the point I have just been making about a much greater focus on developing an intense engagement with the key regional players – all of whom have a common interest in ensuring that the ‘China century’ does not become a ‘China-dominance century.’ We can and should work together to find ways of pushing back against that.

‘More global engagement’ speaks to the obvious point that Australia has opportunities and obligations to lead on issues like climate, arms control, and so on. As I have said, Australia has been a very prominent player in the past, and a significant middle power – much like Canada. It is important, in terms of our own credibility and status as a good international citizen, that we play that role much more vigorously and actively than we have been doing in recent years. That is my quick mantra on how all those different pieces come together.

GB: How is the relationship between Australia and Indonesia today? Where is it headed?

GE: It is okay, but it is nowhere near as strong and intense as it should be. It demands much more of a full-court press in terms of Australian government policy attention. With Jokowi now moving into his second term and looking rather more willing than he was in his first term to recognize some of the regional and larger international realities, the scope for close cooperation with the Indonesians is stronger than it has been for some time.

Of course, the bugging of the phone of the last Indonesia president – Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono – over a decade ago was a spectacular own goal, and some of the memory of that lingers on. This is a difficult bilateral relationship to fully realize, but it needs to be remembered that Australia played a very prominent part in the early Indonesian independence movement, supporting Indonesian independence from the Dutch. As such, we just need to work harder at recreating the intensity of that relationship. The potential is clearly there. There is a long history of quite senior Indonesian policy-makers being educated in Australian universities – particularly at my own Australian National University. There is a lot of capacity on which to build. It really is a matter of just taking the relationship seriously.

Indonesia is, on a number of estimates, going to be up there as perhaps the third or fourth biggest economy in the world by 2050. It is a huge country – the biggest Muslim country in the world. Everything that happens there is of intense interest to us. It is quite remarkable that there is such a lack of public attention to understanding the nature of that relationship.

Indonesia is, on a number of estimates, going to be up there as perhaps the third or fourth biggest economy in the world by 2050. It is a huge country – the biggest Muslim country in the world. Everything that happens there is of intense interest to us. It is quite remarkable that there is such a lack of public attention to understanding the nature of that relationship. It is also disappointing that there has been a failure by successive Australian governments in recent years to recognize fully the extent to which we need to nurture that relationship.

GB: What is the current Australian view of what is happening in the US – strategically and politically?

GE: There is a shared sense of despair about the quality of American political leadership at the moment. It is obvious in the opinion polling and the low degree of trust in President Trump. Evidently, people in high government positions need to be much more circumspect in the way in which they articulate this, but there is a declining confidence about the American alliance being the answer to all of Australia’s potential security problems in the future. I, for one, have never been totally confident that it has been the answer in the past, because I have always taken the view that the Americans are only ever likely to invest blood and treasure in our defence if they perceive it to be in their own interests as well.

On the American side, there is a patent failure to get to the heart of the nature of the current dynamic at work in Asia. It is really going to take an awful lot of effort to rebuild American credibility in the region. Australian public opinion is still supportive of the alliance. There is still a belief that it must be maintained, and that it would be extremely politically perilous for any Australian government – Labor or otherwise – to walk away from that. There are still many advantages for Australia – in terms of intelligence, logistical support and interoperability – associated with the alliance. However, there is certainly declining confidence in the American capacity and willingness to play the traditional leadership role that that country has historically done, and to play the traditionally supportive role that it always has in the global liberal, rules-based order.

The recently signed trade deal between the US and China was a massive new commitment that requires China to buy American exports. It has been brokered in complete disregard of Australian economic interests. I suppose that Canada is in the same boat.

The recently signed trade deal between the US and China was a massive new commitment that requires China to buy American exports. It has been brokered in complete disregard of Australian economic interests. I suppose that Canada is in the same boat. There is going to be a USD $200 billion increase in American exports to China, and that is going to have to come, at least partially, at somebody’s expense. So we have a sense that, at the end of the day, like every other one of the US’s allies, as seen by the current administration in Washington, we are dispensable. We are second-order considerations in the scheme of things. That does not make for a happy relationship, and certainly not one in which one should be making existential calculations.

GB: Over the next five years, how might the US relationship evolve with Australia? What are the good and bad possible scenarios?

GE: Everything will depend on the November 2020 election. If it is a continuation of the Trump administration, I am extremely pessimistic about both the credibility and effectiveness of America’s role in the region and in the world, and extremely skeptical about our capacity to maintain the traditionally very strong relationship that we have enjoyed. There are just too many pressure points, and too many points of ignorance or indifference or unwillingness to recognize legitimate common interests.

The retreat from multilateralism and from a cooperative mindset – which is the only way of dealing with the region’s and the world’s problems – is serious and real. It is, however eminently reversible with just about any of the Democratic candidates now on in play should there be a change in government. But if there is another four years of the kind of experience we have all had, then America will be digging a very, very deep hole indeed – one from which it is difficult to see itself digging itself out in terms of both its global influence and its bilateral relations with important countries like Australia.

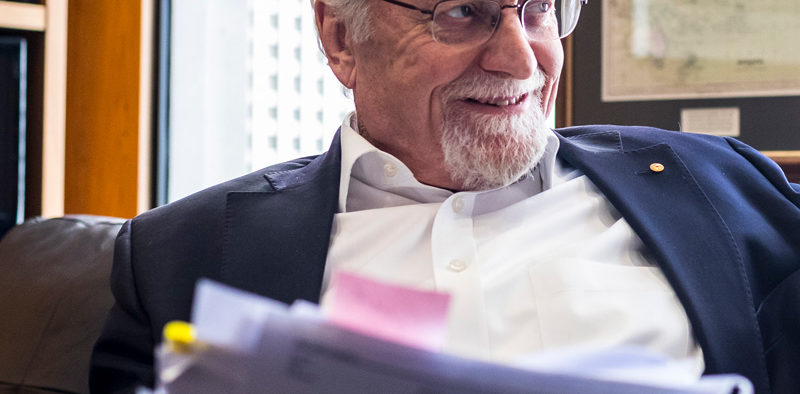

Gareth Evans was Australia’s minister of foreign affairs between 1988 and 1996. He was the founding president and CEO of the International Crisis Group (Brussels), and is Chancellor of the Australian National University in Canberra.