Considerations on International Governance 2.0

What should this new century’s institutions look like? What still works well? What needs reinforcement? What is yet to be divined?

What should this new century’s institutions look like? What still works well? What needs reinforcement? What is yet to be divined?

Just as GB celebrates 10 years, so too does the Institute for 21st Century Questions – 21CQ – celebrate its fifth year of work around the world. Through this work, 21CQ is, in all cases, intensely interested in the renovation of last-century international institutions and, wherever necessary, proposals for ‘new’ institutions, mechanisms and frameworks to solve new-century international, global and even national problems – some of them extremely wicked.

Problem-area ‘Questions’ that motivate 21CQ’s work in the ‘institution-reinforcing,’ ‘institution-creating’ or ‘recreating’ space include the vast Arctic theatre, the former Soviet space, security in West Asia (and indeed in East Asia also) and, to be sure, international criminal justice. Where relevant, 21CQ’s properly national work on 100 million Canadians, the Quebec Question and the Indigenous Question have also clearly fed into and enriched our thinking and effectiveness in respect of the more international challenges. And vice versa, no doubt.

Our work on these various topics allows us now, on considered reflection, to make a handful of observations on what we see, at the dawn of the third decade of this new century, as conceptually essential to the institution game for the coming decades. What kinds of institutions can stitch together our complex world for the pressures of today and tomorrow? What still works and why, and what no longer works? What are some of the new major opportunities for innovation? And what, of course, is still unknown or ‘hard to solve’?

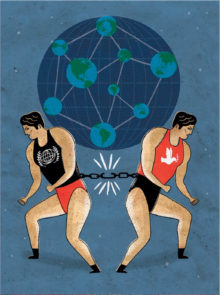

Perhaps the most underestimated and least understood of all new-century international governance challenges concerns the nature of the interactions between

geographical blocs – particularly geographic economic blocs.

Interstitial Institutions

Perhaps the most important and least understood of all new-century international governance challenges concerns the nature of the interactions between geographical blocs – particularly geographic economic blocs, and especially because these blocs, by virtue of their size and membership, before long assume a manifestly strategic character. By contrast, the construction of various species of intra-continental or intra-regional blocs, as discussed below, is more intuitive and builds on extant efforts from the 20th century – the EU, ASEAN, NAFTA, etc.

Also more intuitive is the need for ‘global’ institutions to oversee and regulate all manner of intercourse among states and state-specific institutions – for instance, the UN and the Bretton Woods institutions. We treat the new-century logic and looks for such institutions below.

But what of the ‘interstitial’ relations between geographic blocs? Who is working on these arrangements today? Answer: very few people, and far too few at that.

Far more than considerations about NATO expansion or any state-specific conspiracy, the most persuasive interpretation for the genesis of the Russia-Ukraine-West conflict is that of an essential ‘clash’ or ‘collision’ in 2014 between the competing gravities and ‘fields’ of the EU (the European economic bloc) and the still-embryonic Eurasian Economic Union (the major economic bloc of the post-Soviet space).

These blocs (gravities or ‘fields’) – for all practical intents and purposes, not just economic blocs, but also regulatory, security, normative, spiritual and inevitably, as noted, strategic blocs – pulled on the ‘unclaimed’ Ukrainian space (unclaimed in the sense of not being a proper member of any of the competing blocs) that lay (geographically) between them. The two blocs were able to pull, in opposite directions, deliberately and unwittingly alike, on the young Ukrainian state with sufficient force as to cause its fundamental disruption or destabilization – with chaotic forces released from the Ukrainian ‘atom,’ as it were, as if in a nuclear fission.

Indubitably, then, any ‘solution’ to the Russia-Ukraine-West conflict will require not only a species of restitching of the intra-Ukrainian space to reckon with that state’s young institutions and various constitutional and political specificities, but also an ‘interstitial’ stitching that connects the EU and Eurasian Economic Union between themselves and across the Ukrainian space and state – without Ukraine necessarily becoming a bona fide member of either bloc.

The second major episode of interstitial crisis occurred as late as 2018 – in the event, involving the US, China and Canada, or as between the NAFTA (North American economic bloc) and China (and, by extension, Chinese-led blocs). First, in the fall of 2018, Canada, Mexico and the US signed the new USMCA agreement, intended to succeed NAFTA. This new agreement included – surprisingly, to most analysts, in both North America and Asia – a clause (Article 32.10) that requires each of the three signatory states to have effective approval – procedurally and substantively – from the other two in the event that the state in question should wish to pursue a free-trade agreement with a ‘non-market’ state.

If, as most analysts suggest, this clause intended ‘non-market’ to mean, first and foremost, China (understood as ‘non-market’ in American trade law, but not in WTO terms), then the 2014 interstitial contest between the EU and Eurasian Economic Union over and through Ukraine has repeated itself between the NAFTA and China spaces over and through Canada (and, to a less sharp degree, for now, over and through Mexico). If we presume that it was the US that introduced this clause and logic to the USMCA, then Article 32.10 was intended to place Canada firmly within the NAFTA (North American) economic space to the explicit exclusion of any frictionless possibility of a) joining a China-led bloc, or b) being a member of, or otherwise freely enjoying the economic rents associated with membership in both the North American and China blocs.

Beijing clearly interpreted this clause as hostile to it – by design from Washington, and by subservient or reflexive agreement from Ottawa (and, to a less significant degree, in economic and strategic terms, Mexico City as well).

The interstitial conflict between the North American NAFTA/USMCA bloc and China crescendoed remarkably in late 2018, following the arrest in Vancouver of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, based on an extradition request by Washington for alleged violations of US sanctions laws. The arrest led to a major standoff between Ottawa and Beijing, and has seen the detention/arrest of at least two Canadians in China as possible retaliation for what the Chinese perceive as Canada enforcing an American-led anti-Chinese posture – or, alternatively, as the US using Canada as a key ‘interstitial’ front against China in the North American space or theatre. As we approach the end of 2019 and into the new year, it is not impossible that this front should become increasingly contested, up to and including in quasi-military terms, as these two blocs compete in the near-total absence of proper interstitial governance and understandings.

The key question, then, in institutional and international governance terms, is how to build ‘interstitial’ mechanisms – tendons, as it were – between the major geographical blocs, economic and other, such that the relations and interactions between them are minimally frictious and – to be sure – never hostile to the point of portending armed clash.

In the event, such interstitial tendons will soon have to be divined and developed between, among others, the EU and the Eurasian Economic Union; the North American (NAFTA 2.0) space and China or China-led blocs; the North American bloc and the Eurasian Economic Union across the weakly governed Arctic space (perhaps a near-term next source of inter-bloc conflict, and one treated in a national mini-conference in Toronto this past July, co-organized by 21CQ and the Government of the Northwest Territories); and, lastly, between the EU and an eventual Middle Eastern or West Asian bloc – to which we now turn.

What is the nature or content of these ‘interstitial’ ties or links between blocs? Answer: in the de minimis form, they ought to include joint discussion and problem-solving fora and personnel exchanges (to unwind deep misunderstandings and develop common frameworks), but also, beyond these, a steady stream of pilot projects, joint inter-bloc projects (and commissions), time-limited special economic zones (including under joint or flexible regulation), pushes to coordinate and unify regulatory frameworks, as well as ‘interstitial’ conflict-resolution bodies and arbitrators.

A Security Framework for West Asia

As we have long argued in these pages, there is a pressing need to stitch together the West Asian geopolitical space through more inclusive regional security arrangements. The escalating tensions in the region today – including the growing standoff between Iran and the US in the aftermath of the American withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), also known as the Iran nuclear deal – only underscore the international imperative, and the region’s own conspicuous responsibility, to find immediate and long-term solutions to the wicked security dilemmas of West Asia.

West Asia stands almost alone, among all the world’s major strategic regions, without a region-wide security architecture – one that would allow the region to minimize the incidence of war and reduce the incentives to conventional or even nuclear arms races. The absence of such a security architecture places West Asian states, individually and collectively, at a great disadvantage not only in terms of stability, but also in economic terms given the deep institutional underpinning of modern commercial activity – including the inter-bloc and interstitial relations discussed above.

A sharply divided region, without the institutions, structures, mechanisms and processes in place to facilitate proper emergency communication, security dialogue and cooperation, and – to be sure – conflict management to anticipate and prevent the outbreak of conflict is a region that is doomed to long-term decline.

The existing, non-inclusive sub-regional security structures in West Asia have been largely ineffective in bringing tangible, sustained security to the region. The limited membership, for instance, of the Gulf Cooperation Council, to the exclusion of other littoral states, has hardly stabilized the Persian Gulf theatre – quite the opposite.

Since its founding a decade ago, GB has persistently made the case for reimagining regional security in West Asia. We have called for a decisive move away from zero-sum conceptions of regional security in favour of a region-wide framework premissed on common security, dialogue and inclusivity, floating different algorithms for how the region can incrementally stitch itself together in the service of stability and all the good things that come with it.

Given the historic centrality and importance of the West Asian theatre to the peace and security of all of the connected regional theatres – and to international peace and security more generally – there is great urgency for practical steps to be taken to advance the vision long commended in these pages. On top of thematic conferences and ad hoc public and private interventions in the region, track 1.5 and track 2 work will assume especial significance. The emergence of political heroes to drive these efforts to region-wide success will also be fundamental.

More Asian-Led (Global and International) Institutions

The third major area of novelty in global institution-building this century must be the advent of Asian-led and Asian-initiated global institutions – that is, Asian institutions that are intended to solve international problems within and certainly beyond the local Asian geography or theatre.

China will evidently be a leader in driving many of these new-century international institutions, as with the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). This is only proper, given China’s new centrality in the global system, and should generally be welcomed by other regions as necessary to the international problem-solving mix, where North America, Europe and the former Soviet space have to date been the dominant regions for driving international mechanisms (and rules).

International problem-solving can, in general, only profit from the injection of Asian imagination, initiative and energy. Indeed, it may well be Asia that leads the way in developing early best practices in the aforementioned interstitial governance.

Of course, outside of the aforementioned West Asian dynamic, key regional countries like India, Japan, both Koreas, Indonesia and Singapore will also be possible future drivers of international governance innovation out of East, South and Southeast Asia. International problem-solving can, in general, only profit from the injection of Asian imagination, initiative and energy.

Indeed, it may well be Asia that leads in developing early best practices in the interstitial governance discussed above – specifically, by building on extant and evolving practices in relations between China, the East Asian space, and the Eurasian Economic Union in what may be called the larger or greater Eurasian space.

Could this be expanded to Asian bloc relations with North America? Indubitably. And perhaps starting in the Arctic. A country like Canada has colossal infrastructure challenges in its North, and it is not beyond the thinkable or reasonable that a Canada-China infrastructure-led partnership on Northern and Arctic infrastructure should be the sharp end of the stick both in starting to repair relations between Ottawa and Beijing, but also to begin conscientiously building interstitial links between the continental blocs. (One can imagine Russia, the US and select European Nordic states soon joining this initial interstitial infrastructure ‘consortium’ for the North as a way of deepening these interstitial links across at least four blocs or strategic theatres – to wit, North America, Asia, the Eurasian Economic Union and, of course, the EU.) Let us add, as was raised in the recent national mini-conference held in Toronto, that it is not impossible that the Canadian Arctic – perhaps through a city like Yellowknife – should serve as both a transport and, more globally, psychological hub that connects all of these major Arctic plates, much like Singapore does in Southeast Asia or Dubai in West Asia.

What are other areas, on top of infrastructure, in which China in particular, and Asian-led blocs in general, can lead the way in driving international problem-solving, including the generalization of approaches to other regional blocs? Answer: cyber, space, weapons and armaments (including new-century nuclear, biological, chemical and radiological weapons), oceans, the environment (including climate change) and, to be sure, various species of new technology, science and ethical problems (from nanotechnology to genetics).

For now, based on 21CQ’s consultations, it does not seem like an East Asian or whole-of-Asia security framework is anywhere near to being on the policy table in any plurality of regional countries.

UN and Other Institutions – De Minimis Approaches

While international institutions can and must play an important role in international problem-solving – and, by implication, in national problem-solving in many cases – we remain extremely humble before the reality that ‘formal’ institutions cannot and will never be able to solve all of this century’s major international challenges.

The UN Security Council remains a central component of both global security and global problem-solving not in its ability to comprehensively represent or tackle these problems but rather, in a de minimis sense, because it maximizes the chances of there not being conflict among the great, nuclear-armed powers.

The UN Security Council, for the foreseeable future, remains a central component of both global security and global problem-solving not in its ability to comprehensively represent or tackle these problems with any effectiveness but rather, in a de minimis sense, because it maximizes the chances of there not being conflict among the great, nuclear-armed powers.

More precisely, the Security Council, despite its many imperfections and inability to represent even all the major and nuclear powers of the day (the central question among several important vectors in Security Council reform), the veto powers of the five permanent members (the US, Russia, China, the UK and France) rather ingeniously ensures that there are no conditions under which these leading powers could enter into direct military confrontation between or among themselves under the formal sanction of international law.

In other words, such a great-power war could happen indirectly or illegally, but not directly and legally. As direct war between and among the great powers has, happily, effectively not taken place since WW2 and the very creation of the United Nations, one can only conclude that the de minimis logic of the Security Council, undergirded by a culture of constant assembly, communication and public debate among the great powers, and perhaps also an inference by these great powers in respect of where the approximate spheres of interest (and ‘red lines’) of the opposite great powers lie, has allowed the world to avoid cataclysmic armed conflict on a cross-continental or global scale. Thus far. This would seem to be a good thing.

Of course, there has been – and continues to be – military conflict on a less-than-global or intercontinental scale. This is a less good thing. There has been genocide, there have been many cases of mass atrocity, and there continue to be episodes of illegal war and warfare. India and Pakistan, both nuclear powers and both not permanent or veto-wielding members of the Security Council, still co-exist as border neighbours under the spectre of nuclear conflict.

The Council can certainly do more in respect of atrocity crime prevention, including by lending effective support to efforts aimed at bringing accountability for such crimes. Among the numerous proposals that have been floated to this end is that of a Security Council Code of Conduct that essentially calls on Council members to refrain from voting against fit-for-purpose draft resolutions intended to prevent and address atrocity crimes. Over 100 UN member states – including P5 countries like France and the UK – have signed on to the Code.

But these performance gaps do not compromise the grand function and utility of the Security Council – as the Council, by its very logic, does not and cannot promise to eliminate these major problems. It is not a de maximis structure. And so we can certainly improve on the representativity and operations of the Security Council at the margin, but it is not Security Council reform as such, or even improved operations or functioning or the ‘good will’ of permanent members (or the removal of so-called ‘capricious vetoes’) that will serve as a panacea to solve the world’s major problems outside of the core imperative of preventing military cataclysm.

If the Security Council plays its due (minimalistic) part, then there must be other international mechanisms and institutions that build on its foundation (or ‘understructure,’ as it were) in order to address broader issues – non-war and war alike. And indeed, there are many, including the new-century variants we discuss above.

Still, we should like to stress that the classical logic of the late Australian Hedley Bull, in his precocious book, The Anarchical Society (1977), continues to play an important role in expanding the de minimis logic of the Security Council to the following types of mechanisms and informal ‘institutions’ that allow the essential ‘anarchy’ of the world to become a quasi-‘society,’ as it were:

- war (yes, war or force as an international mechanism – and hopefully one that, as discussed below, can be driven to a minimum this century)

- diplomacy (in both its classical and evolving forms)

- international law (to which we now turn)

- balance of power

- great powers

We support the basic logic that these institutions, working in varying combinations, continue to provide the central mix of means to the end of solving most international problems. This means that international law, while clearly important to human and state conduct around the world, cannot alone solve pathologies like war, genocide and a host of non-military challenges (many of which are noted above). It is a necessary condition, but it necessarily also operates in combination with mechanisms like diplomacy (led by conflict mediation), great-power balances and even the pressure of potential war or the legal use of force in order to drive various outcomes that tend toward resolution of international problems. However, the relative weight of war and the threat of war as an ‘institution’ in international affairs must be driven conscientiously to a minimum. The principles of jus ad bellum, consistent with the UN Charter, and jus in bello must therefore become increasingly accepted in practice and consistently applied. Much international progress has been made in this regard, but much work remains still to strengthen the institutions, instruments and the will and capacity of nations to ensure regular and effective adherence and enforcement.

There is perhaps no development more consequential in this regard than the adoption of the Rome Statute in 1998 and the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC was created – in the aftermath of the atrocities of WW2, the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and other wars and conflicts – as an independent, treaty-based judicial institution that would aim to hold individuals criminally responsible for the world’s most egregious crimes – to wit, genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression. The Court’s jurisdiction over the crime of aggression was triggered last year.

Over 120 states have ratified the Rome Statute. With the ICC, the system-wide message is that the unchecked commission of mass atrocities to advance political objectives is no longer an acceptable norm – or that, at a minimum, there is a normative push in the opposite direction, toward greater accountability, regardless of persona or rank. In this sense, the ICC, as a central institution of international criminal justice in particular, and international law more generally, plays a critical stabilizing role in the broader international system. It also doubtless plays a material role in atrocity and conflict prevention through general and specific deterrence.

The ICC’s operating environment is evidently complex. It does not have a monopoly on accountability for atrocity crimes – that is, it acts only where it has jurisdiction and serves as a court of last resort. The primary responsibility for investigation and prosecution still rests with national authorities. Bref, for the Court to perform consistently and succeed over the long run in delivering its mandate, it must continue to act strictly within this mandate, jealously guarding its independence and impartiality, drawing regularly on the cooperation of states, the UN, regional bodies and other relevant stakeholders.

And yet we must allow, on this logic, that some problems of an international order will not be solved in any meaningful way, and some wars not avoided. The circle of mechanisms and institutions expands from the de minimis and critical, in other words, toward the desirable, but always short of total coverage. The magnitude of the gap of unsolved problems turns on the ambition and imagination of humankind this century – and whatever cannot be solved in spite of an existing ambition can only be described, existentially, as part of the tragedy of life and the world.

Let us also note, perhaps with emphasis, that the present fashion of invoking a so-called ‘rule of law’ tradition in some parts of the world as, by dint of multiplication or replication to all quarters of the world (perhaps in almost identical or universal form), the necessary ‘telos’ or end-state of international relations this century, misses the point of both the de minimis logic of the Security Council in particular and the five or so Bullian ‘institutions’ radiating outward in concert with that de minimis structure. ‘Rule of law,’ even in its maximal form globally, still must work in concert with the other institutions of international society or the international system if it is to be effective. The goal, of course, should be to maximize the reach and interoperability of these institutions, and refining them constantly – hopefully in the service of a better global condition; or better still, peace.

The GB Team wishes to thank our readers, writers, artists, friends and supporters around the world. We hope you continue to enjoy your Brief.