AMLO and the Future of Mexico-US Relations

The future is pragmatic, provincial and opportunistic, rhetoric and reputations notwithstanding

The future is pragmatic, provincial and opportunistic, rhetoric and reputations notwithstanding

The last couple of years have marked the lowest point in Mexico-US relations since 1914, when President Woodrow Wilson ordered the occupation of the port of Veracruz by the US Navy. The election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, or AMLO, as president clearly opens the possibility of significantly improved relations between two of North America’s three giants.

To understand why this is so, one first needs to ditch the notion that AMLO’s victory in the presidential race was some sort of Mexican response to the election of President Trump in 2016 – an oft-repeated supposition in the English-speaking media grounded in the mistaken idea that anti-Americanism is second nature to Mexicans.

While the Mexico-US relationship – much like the Canada-US relationship – has always been complex, defined by a long, shared border redrawn by war in the 19th century, the facts on the ground speak to the Mexican people having established enduring bonds with el Norte. To be sure, the reverse is also true. As the former US ambassador to Mexico, Jeffrey Davidow, wrote in his memoirs, The Bear and the Porcupine, there is no other country that is as important to the US as Mexico. According to Davidow, the number of daily economic, political and cultural exchanges between these two countries is unmatched in the world.

In the build-up to the 2018 Mexican presidential election, commentators on both sides of the border repeatedly pointed out the similarities in style between AMLO and Trump – both inflammatory and anti-establishment – and anticipated a head-on collision between the two leaders. And yet these commentators may have underestimated AMLO’s principal characteristic – that of a pragmatic, professional and, by reputation, calculating politician. As such, we believe that, on the balance of probabilities, the new president of Mexico is better placed to improve the relationship between Mexico City and Washington than his predecessor, Enrique Pena Nieto.

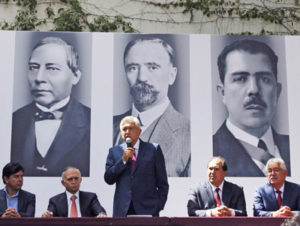

But how and to what end for Mexico? Despite running for president as a populist outsider, AMLO is in fact a full-blooded political animal, with more than 40 years of experience in the craft. He became involved in politics as early as 1976 in his native Tabasco after completing a degree in political science at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City. Shortly after returning to his home state, he joined the local chapter of the Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI). He has been involved in party politics ever since: with the PRI for 12 years until 1988, after which he joined Cuauhtemoc Cardenas and his leftist National Democratic Front (FDN), which would eventually become the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).

For the next 24 years, AMLO was a key PRD figure, having twice been candidate for governor of Tabasco (1988 and 1994), the party’s national president (1996 to 1999), mayor of Mexico City (2000 to 2005), and a presidential candidate in both 2006 and 2012. It was only after his second attempt at the presidency that he parted ways with the PRD in order to found his own political fraction – the Movement of National Regeneration, or MORENA, which obtained legal recognition from the electoral authorities in 2014. And it was under the MORENA – for all practical intents and purposes, a one-man party – that AMLO won the presidential elections in July 2018.

Bref, AMLO has been able to survive the ups and downs of his profession. While he has been in the Mexican national limelight for an extended period, he has also been able and happy to jump ship when necessary – opportunistically, as it were. One could reasonably presume, then, that the new Mexican president enters office with the working hypothesis that there is little to be gained, politically and in policy terms, from an open confrontation with President Trump – and perhaps a great deal to lose. His own approval ratings will largely depend on the strength of the Mexican economy, which is wholly dependent on the preservation and management of a robust commercial relationship with the US, its largest trading partner. (Mexican exports to the US totalled US$340 billion, or nearly 80 percent of the country’s total exports, in 2017.)

AMLO has already given some indication of an interest in avoiding friction with the Trump administration. Shortly after his election victory, he hosted a delegation at his Mexico City headquarters that included top US officials like Jared Kushner, Mike Pompeo, Steven Mnuchin and Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen. He named Jesus Seade as his representative during the now concluded talks on the new USMCA trade agreement between Mexico, the US and Canada. Seade, a former WTO economist, is believed to have played a decisive role in softening Mexico’s demands, helping to push Mexico City and Washington – after lengthy negotiations – to a preliminary bilateral agreement ahead of the more general trilateral agreement with Ottawa. The US President tweeted shortly after the agreement: “New President of Mexico has been an absolute gentleman.”

So whence the idea of AMLO as a political outsider? Answer: from AMLO himself. During his many years in politics, the new Mexican president has been very good at presenting himself as if on the margins of political power, and specifically as the only moral man (left standing) in Mexican politics, whose life goal is to take on the corrupt and powerful elites (or what he calls the “mafia of power”). And yet, as mentioned, AMLO has been at the heart of Mexico’s traditional political elite since at least 1996, when he first entered the national political stage as the president of the PRD.

In terms of foreign policy, this will likely translate into an inward-looking Mexican government with little interaction with world leaders and heads of state – other than as strictly necessary, as with President Trump. At the margin, the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Venezuela will likely force AMLO to take a position in respect of the Maduro regime. The relationship between Mexico and the Vatican may also be tested, as AMLO tackles domestic issues like same-sex marriage, women’s rights and, further to the new USMCA, labour rights.

Of course, on the meta-relationship between Mexico and the US, the central question for Mexico is whether the initial mutual goodwill between AMLO and Trump will endure. The new USMCA trade agreement suggests that both AMLO and Trump are at core political pragmatists – rhetoric notwithstanding. But if pragmatism reigns in matters economic, what of immigration and migration – a key issue for both Mexico and the US, and one on which bilateral cooperation is indispensable and unavoidable? If Trump was elected on the commitment to ‘Make America Great Again,’ promising to solidify the US southern border against undocumented migrants (with particular emphasis on Mexican nationals), then AMLO vowed during his campaign to stand up to Trump’s anti-Mexican rhetoric and provide assistance to Mexicans living in the US. Still, both leaders are now hinting at the possibility of framing undocumented migration not as a US-Mexico bilateral issue, but rather a hemispheric one.

On the evidence, a hemispheric approach to American border preoccupation would appear to be sensible. According to a 2018 report by the Pew Re- search Center, Mexican migration to the US has been negative since 2014.The main source of undocumented migrants moving into the US today is Central America’s Northern Triangle, comprising El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Unlike the Mexican diaspora that is pulled into the US by higher wages, the primary driver of this Central American migration is the criminal violence in the Northern Triangle countries – a driver that makes migrants less susceptible to deterrence by enhanced security measures at the Mexico-US border, and explains why the US has put pressure on the Mexican government to ‘thicken’ its southern border with Guatemala and ramp up security in the border states of Tabasco and Chiapas.

Mexican-American cooperation on migration is effectively guaranteed under AMLO. He will be happy to allow Washington to set the macro-logic of border relations in exchange for trade and other economic rents for Mexico – or at least in order to avoid tariffs and commercial restrictions. This dynamic will likely contradict AMLO’s electoral pledge to the effect that he would not detain Central Americans crossing Mexican territory to get to the US border. But this also means that, despite AMLO’s larger disinterest in foreign affairs and external strategy, Central American countries will definitively need to be at the negotiating table on migration, and that both the US and Mexico will need to work with them to curb the high levels of criminal violence in the region.

There are – to be sure – still many unknowns about how AMLO and Trump will conduct the Mexico-US relationship. AMLO once proposed amnesty for drug cartel leaders – something that could not possibly sit well with President Trump, who has famously said that the US receives many “bad hombres” from Mexico. Both men will be keen to continue to cultivate their anti-establishment bases, but their pragmatic tendencies might just produce a better relationship than many would expect.

We expect no state visit to Washington or Mexico City anytime soon, but we do expect an intense bilateral, technical agenda driven by top officials working on the political oxygen provided by both national leaders – other things being equal even after the American mid-term elections. Let us call this la diplomacia del silencio. Even on the subject of the dividing wall between Mexico and the US, so coveted by President Trump, AMLO’s governing instinct will be to stay busy at home and avoid frontal collisions with the US – allowing Mexico to steer toward new horizons in the medium term while weathering any continental storms in the shorter run.