Reasons for Staying Together

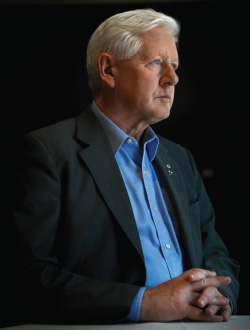

GB sits down with the former federal opposition leader and Ontario premier to discuss Quebec, Scotland, Sri Lanka, statecraft and all that

GB sits down with the former federal opposition leader and Ontario premier to discuss Quebec, Scotland, Sri Lanka, statecraft and all that

GB: If there is a secession referendum in Quebec next year or the year after – something that is not impossible – what would be the key arguments for keeping Quebec within Canada?

BR: My view has always been that we need to present the federal option to Quebecers as giving them all of the advantages of a very high degree of autonomy – something that they already enjoy within the federation – and all of the advantages of a powerful association with the rest of the country. That is the best argument. Nehru used to refer to the Commonwealth as ‘independence plus.’ Canadian federalism is exceptionally devolved. The provinces have a great deal of responsibility for key areas of public policy, and Quebecers have a lot of room to manoeuvre within that federal structure. Absent that federal structure, Quebec becomes a diminished place – a more closed society; more impoverished economically, fiscally and financially. There is no economic argument favouring independence for Quebec.

Of course, we cannot predict what the reaction and feelings will be in the rest of the country in the event of a referendum – or in the event of secession. That is always something that people should not underestimate. For instance, there is no reason why Quebec, post-secession, should enjoy the advantages of Canadian currency.

I have been arguing in Ottawa and elsewhere, for a long time, that the Quebec dynamic is simply not something of which we can ever lose sight. As a country, we have certainly taken our eye off of this issue, and such absence of attention always allows mischief to flourish.

GB: What are the key advantages from which Quebec profits within the federation?

BR: The first one is that Quebecers are part of a great country called Canada. I think that the benefits and pride of being Canadian are very strongly embraced by Quebecers. I do not believe for a moment that the idea of Canada or that the emotional arguments about Canada are without considerable strength. Second, there are countless practical advantages for Quebec and Quebecers. There is plainly the advantage of being part of a bigger group – a bigger economic and geopolitical unit – that, at the same time, allows for a great deal of autonomy within the federation. There is no need to apologize or improvise at the last minute in respect of the arguments for unity. We simply need to talk much more directly about the real advantages of the federation.

GB: What is the import of the upcoming Scottish referendum for a possible Quebec referendum?

BR: Scotland is just one case in point in the steady rise of local nationalisms in Europe. This, broadly speaking, is a cause for concern. I always think that the return to ethnic identity as the basis for citizenship is problematic. I am a big believer in the reality of pluralism. Every society is plural, in some sense. Countries that think of themselves as being made up of only one language or one identity are really not – that is, people are always more diverse. I think that the borders and boundaries between countries, with some great exceptions, are becoming more and more artificial, and sovereignty much less of an absolute than it has ever been.

Still, one of the reasons for which Canadians and Quebecers need to take an interest in what is happening in the UK is that, given our connections with Scotland and the United Kingdom, we have much at stake in reinforcing the advantages of association and unity and connection. Britain is becoming a more devolved society. It is not yet a truly federal country, but it will get there. There are many arguments as to why power should be devolved to local legislatures or to the Scottish parliament or Welsh parliament. Those all make sense to me, but the notion of breaking away entirely from London makes a lot less sense.

GB: What is the nature of the Aboriginal question in Canada in this early new century? How would you frame it?

BR: The issue is: how do we build institutions that are based on respect? Canada is not there yet. Our institutional base and our constitutional base doff their cap to respect, but there are many other very powerful historical forces at work that are not respectful and have not been respectful; in fact, they are based on conquest and racism. They have been based on an attempt to belittle or simply assimilate, and have ultimately proven to be disastrous. They will continue to be disastrous as long as they are embraced. As such, it is going to take some fundamental changes at the federal and provincial levels in terms of governance in order to make sure that the dignity of First Nations people is recognized, and that their desire for self-government and greater autonomy and greater control over their own lives is met. If these aspirations are met, I am certain that there will be greater opportunities for general prosperity and for personal success for Canada’s Aboriginal people.

GB: What would be some of the basic moves that federal and provincial governments would need to make?

BR: We have treaty structures that are partially negotiated by province and partially negotiated by the federal government, based on the 19th century and pre-19th century premise that we needed to limit and assimilate First Nations people. Those treaties have to be revisited and renovated in a major way. This is the story across a large part of Canada today. At the federal level, we have to embrace more clearly what devolution and greater responsibility for First Nations will look like. We have to send unconditional signals to the effect that the sharing of power and the creation of economic and social partnerships have to be the way forward – replacing what is essentially a colonial structure. There are three central pieces to this colonial structure and heritage. The first is the Indian Act. The second is the treaties. The third is the institutional base, at the heart of which is the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (now Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada), which really should not exist in the 21st century. There must be a complete rethink about how these governance relationships work.

GB: Is there a tension – short-term or long-term – between devolving respect or authority or resources to individual Aboriginal nations – big or small – and the ability to preserve a coherent, operational Canadian federation?

BR: No. Canada’s federal structure has nothing to fear from its current devolved structure. This is actually quite an effective form of governance for a country that is as big as ours – as geographically large and as diverse in demography. The historical price that we have paid for paternalism and a lack of accountability and responsibility in relation to the Aboriginal people has been very high indeed. We are continuing to pay it. No one, in assessing the state of the relationships between Canadian governments and Aboriginal people, can argue that what we have done over the last 200 years has been a success.

GB: What does the path to success on this issue look like in coming decades?

BR: It must involve much more effective regional government, just as we are seeing in Quebec. Ironically, the two provinces that had not originally signed treaties with First Nations – Quebec and British Columbia – have made the most progress on new models of effective governance. The Nisga’a Treaty and the James Bay Treaty, for instance, are modern treaties that are based on respect, economic partnership and self-government – that is, on a real sense of how things are supposed to work. However, if you look at the map of Northern Ontario, First Nations people have exceedingly little responsibility and very little say in what goes on. In other words, they have very little capacity to govern themselves. The result has been quite disastrous from the point of view of social development.

GB: You have done much governance work in, on and for Sri Lanka. What is the state of affairs in Colombo and the rest of the country today? Does the country have a federal future?

BR: It is difficult to assess what is happening on the ground. The government in Colombo is largely tied to the sentiments of the majority ethnic group. It is a Sinhalese nationalist government. It is an authoritarian government. It does not brook dissent or difference of opinion. It has used military conquest as a substitute for creating institutions based on respect. It won a civil war. It succeeded in achieving a military victory over a guerrilla army. But it has not succeeded in uniting the country in a way that is based on mutual respect. As such, the government will continue to have problems convincing the world that positive change is underway. Despite the military victory, the government is going to find that the fundamental problems have not disappeared – that is, that there remains the basic fact that, in the north and the east of the country, there is a group of people who speak a different language and practice a different religion and are looking for institutional presence in the country. At present, this group does not see or feel such institutional presence and representation. On the contrary, it sees the national symbols that have been created by the new government as symbols of conquest. This just creates huge hardship for the losing minority, and will be a drag on the prospects for the country as a whole.

GB: Who are the two or three most impressive leaders – globally, democratic or other – in this early new century?

BR: Two leaders have been outstanding in the early part of the 21st century. We have lost them both: Vaclav Havel and Nelson Mandela. Both established a standard of understanding, lucidity, eloquence and inspiring leadership that has been quite phenomenal in transforming the politics – or at least the ideals – of Eastern Europe and Southern Africa and indeed the world. Both of their leaderships are based on a powerful commitment to open societies and to really understanding the forces at play in complex theatres. In the case of Havel, he understood that the national and social structures in Stalinist, communist societies could never withstand scrutiny or become sustainable because of the repression and corruption on which they were based. In the case of Mandela, he was speaking out against a system of institutionalized racism that simply was not sustainable in the modern world. However, in so doing, he certainly was part of broader, more radical thinking – a rethink even for himself – that was essential in coming to terms with differences in society and the idea that one could not simply impose a kind of black nationalism on a country as diverse and complex as South Africa.

GB: Is it possible to have great leadership in a non-democratic or less-than-democratic context?

BR: If you look back at recent history, you can say that the greatest revolutionary figure in China was not Mao Zedong, but rather Deng Xiaoping. Deng understood that if China’s economy did not become more open and China did not more generally embrace the need to be more open to the rest of world, then Chinese society would become chaotic – even more chaotic than in the last years of Mao and during the Cultural Revolution.

There is no question, then, that Deng was a great leader. He was a communist – a member of the Communist Party of China – and worked within that structure. He made no apologies for that – that is, he knew who he was and what he stood for. Still, he understood that things needed to really change in China.

Within authoritarian or communist or dictatorial societies, there are degrees of openness that, fostered by great leadership, can sometimes create the basis for significant change. On the other hand, if you take somebody like Vladimir Putin, I think that he has become a huge disappointment. Although he started off in the post-communist period in Russian history, he shows all of the signs of reverting to a very authoritarian and top-down style of thinking and governance. That is very worrisome for Russia and indeed possibly for Europe.

GB: What about great leaders among the living?

BR: In the US, President Obama has shown an extraordinary capacity for eloquence, for setting a tone, and for trying to set a direction for his society and his country. It is too early to tell whether he has been or will be a great president. Nevertheless, I do not think it too early to say that his election and his approach to governing are a testament to the general openness and dynamism of American society. Having said all of this, if you look at politics in much of Western Europe and North America – in democratic countries – this is not a time in which great leaders have stood out. We cannot say that.

GB: Is there a reason for this dearth of greatness?

BR: There are many reasons. The context in which politics happens today is extremely complex. The 24/7 news cycle, the power of money in political contests, and, among other things, the difficulty of making decisions that will last, make it harder.

![]()

Bob Rae is the former Premier of Ontario, former leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, and a professor in the School of Public Policy and Governance, University of Toronto.