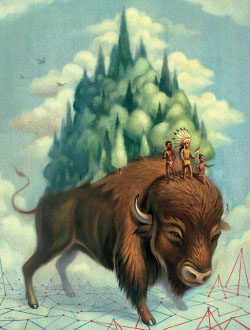

Toward an Aboriginal Grand Strategy

Classical wampum diplomacy may be dead and gone. But North America’s Indigenous people are once again power players

Classical wampum diplomacy may be dead and gone. But North America’s Indigenous people are once again power players

European explorers were startled by the architecture, economies and cosmopolitan empires that they encountered in what they termed the New World. From present-day South America, through Mexico, and into core North America, the continents teemed with Indigenous people. Brutal conquest moved quickly in South and Central America, but in North America, British, French and Dutch explorers and settlers had to adapt to the pre-existing diplomatic protocols and norms of Indigenous nations. For three centuries, the business of treaties for land, war-making and peace-brokering was all conducted according to Indigenous procedures and expectations.

Contagion, more than any other factor, made possible the eventual ascendancy of the settler people. Indigenous communities succumbed en masse to diseases to which they had no previous exposure, and thus no immunity. Settler governments, in turn, implemented policies aimed squarely at the extermination of Indigenous people in the Americas – with notorious consequences: massive theft of Indigenous lands, wholesale displacement of Indigenous communities, confinement to poverty-stricken reservations, and the standing up of a residential and boarding school system that, by force of law and arms, systematically taught entire generations of Indigenous children to be ashamed of their cultures, robbed them of their languages, and estranged them from their families and the lands that had sustained their communities from time immemorial.

And yet today, in the year 2013, Indigenous people are resurgent: their claims to protection of their lands and interests are increasingly being heeded by the courts. Indeed, these Aboriginal interests are intersecting decisively with the economic interests of states and the profitability of major companies. The Indigenous political philosophy that once dominated diplomatic protocols is returning to prominence – not only among and for Indigenous people, but as a hard lesson for domestic and foreign investors who have forgotten that their ancestors arrived in a complex web of pre-existing relations that is now assuming a 21st century integument.

Europeans arrived in the New World cold and hungry. They entered a world of thick forests, seas overflowing with fish, and vast tracts of land inhabited by a rich, diverse, cosmopolitan Indigenous population that had, in the context of a dense network of political relations, been engaged in inter-tribal trade and international diplomacy (and war) for hundreds – perhaps thousands – of years before the first European set out across the Atlantic Ocean. Lacking the force of arms, numbers and local knowledge, the settler people could do little but submit to the incumbent diplomatic, political and strategic order. As such, Indigenous diplomatic practices dominated interactions between Indigenous nations and the settler people for three hundred years – until such time as the settlers determined that they no longer needed Indigenous allies to survive and thrive on Turtle Island (the name given by Indigenous people to the continent that the settler people call North America).

Prior to the 19th century, in the unfolding drama of the early and middle contact periods, Indigenous nations were, in relation to the settler people, variously military allies, political partners and independent actors. Diplomacy was undertaken according to Indigenous protocols, and alliances with Indigenous nations were often the difference between war and peace, victory and defeat. The Dutch, English and French all entered this New World not as masters, but as students. Europeans lacked the necessary ken to sustain their communities – ignorant as they were of the cycles of weather, the soil and growing seasons, as well as the animal and fish migrations of Turtle Island. In order to survive on Turtle Island, settler people had to take up the customs and habits of the Indigenous nations who met the settler people on the shores of a bustling Indigenous empire.

In contrast to the cold, wet and utterly dispiriting experiences of early settlers, the Indigenous residents of Turtle Island were manifestly at home in their own cosmopolitan empire. Prior to the arrival of the Europeans, First Nations had developed a robust set of diplomatic norms to govern their relations with one another. The political order into which Europeans entered was based neither exclusively on consent, nor on conflict, but on a considered balance of both. Conflicts were not uncommon between Indigenous nations, and wars were frequently brutal and bloody. Peace, however, was a very well-regulated part of the strategic and diplomatic landscape. When one nation defeated another, a condolence ceremony would be held by the victor in order to recognize the losses of the defeated. Among the Haudenosaunee, the victor would use wampum belts to literally ‘wipe away the tears’ of the defeated. (From these ceremonies comes the phrase ‘to bury the hatchet’ – because a hatchet would be buried by both parties beneath a tree of peace.) Defeat meant not subjugation, but a realignment of political interests. The victor was said to be the big brother in the new relationship, and thus was afforded some political say over the actions of the little brother. However, as big brother, the victor was also expected to look out for his weaker sibling.

Too often today we forget that from the late 1490s (the arrival of John Cabot) until the earliest decades of the 1800s, international diplomacy on Turtle Island was conducted according to Indigenous – not European – protocols. These diplomatic protocols, known as wampum diplomacy, involved the exchange of belts and strings of beads called wampum in a complex set of customs, interactions and expectations that governed the relations between nation-states. Wampum were not merely gifts: the exchange of wampum signalled intention and certified agreements. Wampum served as mnemonic devices that, in their beaded patterns, encoded the contours of commitments between parties.

The language of Indigenous international diplomacy is tied directly to the land and the various ‘other than human beings’ – animals, plants, trees, rocks, insects – that inhabited Turtle Island, bound together in an all-pervasive ecology. Indigenous nations regarded themselves as part of these landscapes, and divided themselves into family clans based on animal totems in order to represent their place in the geography and spirit of the land. This set of relationships between Indigenous communities and the land and animals around them was known as the web of relations. When Europeans arrived in Turtle Island, the presumption of First Nations was that these newcomers would have to be welcomed and brought into the existing order of things – that with help, the Europeans would eventually find their own place in the web of relations on Turtle Island.

For three centuries, that is largely what happened. Indigenous diplomatic protocols in the form of wampum or pipe ceremonies dominated virtually every meeting between the Europeans and Indigenous people. The British rapidly came to understand that wampum diplomacy was necessary in order to broker treaties of peace and friendship with Indigenous people, conduct land sales, and negotiate safe passage in potentially hostile territory. And so while the British never fully mastered the art of wampum diplomacy, they became effective practitioners of Indigenous diplomacy through the ritualized presentation and reception of wampum belts and beads.

Of course, the end came abruptly for the Europeans vis-à-vis the web of relations. By the end of the War of 1812, Indigenous nations in Canada were no longer needed as military allies. In the US, Indigenous people were regarded not as allies, but as enemy landholders who stood in the way of national expansion (manifest destiny). Besides, by the early 19th century, the settler people had established supply lines with their home nations, and had sufficiently ‘tamed’ the geography and environment of Turtle Island to ensure their own survival. The settler people largely put aside Indigenous diplomatic protocols. They began instead to pursue diplomacy in a European idiom, using boiler-plate treaties the terms of which were set out in London, Ottawa and Washington, and the procedures of which, if they at all incorporated Indigenous traditions, did so merely as ceremony. In the US, where treaties were routinely made and then broken, the government finally settled on a programme of conquest, occupation and subjugation doled out in equal measure.

To be sure, the US never regarded itself as an older brother to the conquered Indigenous nations as it would have under the rules of wampum diplomacy. The US and even the Canadian and British governments wiped their hands clean of the web of relations, and installed themselves as masters of their new world. The volte-face was complete. Indigenous people were, in the ensuing years, confined to reservations and boarding or residential schools. History books – certainly those books used in elementary and high schools – edited out any trace of the old order. Indigenous people were relegated in both popular and academic culture to prehistoric ‘savages’ to whom nothing was owed, and whose eventual extinction was both assured and desirable. The web of relations was forgotten, treaties ignored, the covenant chains rusted, and the wampum belts and beads exiled to museums to gather dust.

The legacy of this neglect is today evident in the shocking socioeconomic statistics of Indigenous people, as compared to the settler people: poorer health outcomes, greater unemployment, vast overrepresentation in the prison system, communities without potable water or elementary schools, higher rates of suicide (especially youth suicide), addiction, poverty, and endemic lack of adequate housing.

Despite this socioeconomic picture, Indigenous groups across the globe have begun to reassert their rights. They are aided in these efforts by domestic and international law. In Canada, Australia, New Zealand and several Nordic countries, Indigenous rights are increasingly recognized by the highest courts in the land. The courts are affirming Indigenous rights (or title) to their traditional lands. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was signed by 144 nations. It recognizes the cultural, linguistic, political and economic rights of the world’s Indigenous people. The interconnection between Indigenous people and their lands has been recognized in unique ways. In New Zealand, for example, the Whanganui River itself has legal standing to sue in domestic courts under an agreement between local Indigenous groups and the New Zealand Crown.

Implicit in these domestic and international orders are Indigenous understandings not only of their rights against others, but of Indigenous peoples’ continuing place in the web of relations. The demographic dominance of the settler people has not altered Indigenous political philosophy, and Indigenous people thus reassert their rights in order to perform their roles as stewards of the land, and as actors within a web of relations that the settler people too often regard merely as a landscape from which resources (or utility, or rents) can be extracted.

In Canada, recent months have witnessed a vast uprising of Indigenous people marching under the banner of Idle No More. Protesters are demanding action from governments to address the social and economic conditions of Indigenous communities and, relatedly, to obtain greater protection of their lands and resources. These protests have so far been peaceful, but frustration is visibly building. The fact is that in large countries like Canada, national infrastructure – for instance, railways and pipelines – cannot possibly be secured against an insurgent Indigenous population, across whose territory these steel ribbons stretch for tens of thousands of miles (especially when there is virtually no state presence of any kind to counter such an insurgency).

What the settler people need to come to terms with now is not the conceptual contours of Indigenous political philosophy – robust and as worthy of study as this philosophy may be – but rather the practical reality of the web of relations in an evolving international order. Consider that when global actors invest in Canadian or Australian mines – or indeed, when Canadian mining companies seek to operate in Latin America – they do so on the premise that title to the lands and resources is assured. Increasingly, that premise is being called into question, as Indigenous people use domestic and international law, the press and the mechanisms of environmental activism to shut down mine sites, end clear-cut logging, and push back against risky proposals for hosting pipelines on their territories. In these increasingly common circumstances, global capital cannot ignore the web of relations, because the global economy quite simply is, in the end, part and parcel of this web of relations: bref, European and Asian capital is now closely intertwined with the fate of Indigenous people, whose lands and resources foreign investors seek to exploit. Indeed, North American capital faces very similar uncertainties in Central and South America.

The web of relations is a statement of fact about the interconnectedness of the global order. Oil requires pipelines; paper companies need forests; mining companies need not only minerals, but vast trailing ponds that blight landscapes. These and all modern investments in resources require a geography that is hospitable to development. In the past, states had the force of arms and laws on their sides. Today, we recognize that such force of arms is politically untenable and morally bankrupt. Law, in the meantime, has come to recognize Indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands.

Environmental activists also understand that in siding with Indigenous people, they are siding with those who will protect the clean drinking water that we all need to survive. They presume – probably correctly – that while today’s battles are over resources like gold and oil and diamonds, tomorrow’s battles will be for the aquifers and watersheds that fuel not only our economy, but our own bodies.

Science, too, is increasingly coming to terms with the web of relations. Pollution is no longer framed as a regional problem; it is a global issue. Global warming is not caused by any one nation: the effects of a warming planet will be felt by all of us as sea levels rise, and the seas themselves begin failing to support the aquatic biodiversity upon which so many people around the world depend for basic sustenance. Indigenous people have long understood that we are, quite literally, all in this together. The environment, on this logic, is not some external element; rather, it is something of which we are all a part. We are all in the web of relations.

None of this is to say that Indigenous people will oppose every resource development project that comes to their lands. Indigenous people will want to know that when their lands are used, they will be used in a way that spreads economic development to local Indigenous people, and that the development itself will occur in a manner that does not destroy the lands that have sustained Indigenous people for thousands of years. Economic development matters – especially given the poverty endemic in contemporary Indigenous communities – but the web of relations is not merely a relationship among mortal contemporaries. The web of relations stretches backward and forward in time, honouring the traditions of our ancestors, and preserving the land and its riches for the generations still to come.

Economic development on Indigenous lands is clearly possible. But the old ways of doing business are over. It is no longer sufficient – or even workable – for foreign or domestic investors to work solely within the economic, political and legal frameworks of the settler nations. Permission from local communities must be sought. Their interests must be accommodated, and their concerns addressed – particularly when it comes to land and its sustainability. Indigenous people have been too long ignored, their economic interests marginalized, and their access to the basic rights of citizenship – particularly rights relating to private property and security of the person – undermined. In many cases, therefore, rather than relying primarily on states to look out for their interests, Indigenous communities are seeking and privileging direct agreements with resource companies and foreign investors. These agreements – often termed Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs) – set out what are effectively contractual promises to ensure that economic development in the form of jobs, cash and infrastructure flow to Indigenous communities and citizens. IBAs represent the new order – new diplomatic protocols, as it were – for a new century. New protocols and norms will doubtless soon follow and gain acceptance, as circumstances dictate – that is, as new resources are discovered in traditional Indigenous territories, and as investors consider the option of pouring money into these projects.

The new order is a return to the ancient recognition that the web of relations is both political philosophy and practical reality. This requires more than government permits and state permission. Increasingly, international and domestic investors will find that the only way to secure long-term investments is to spend time going into Indigenous communities before they even apply for permits and other approvals. In other words, talking to Indigenous leaders and their elders is now the responsibility of global enterprise. It is the only way to guarantee the safety of international investments, and the only proper way to find one’s place in the global web of relations.

![]()

Douglas Sanderson is Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Law, University of Toronto.